Chapter Text

. ݁₊ ⊹ . ݁ 𓅪 ݁ . ⊹ ₊ ݁.

And so the star-sisters shed their dove-wings by the pool and dipped into it as women. The Cowherd, desiring them, stole one’s garb. That celestial weaver of cloud-floss became his wife; and her keeper, bereft of her sunset-polychrome cloth, stole the weaver back to the heavens. This cruel mistress stranded husband and wife on opposite banks of the Silver River that glimmered to life at night. But there too was the mercy of magpies when, once a year, those beating wings would span the River and bridge the lovers so they would no longer be kept apart.

. ݁₊ ⊹ . ݁ 𓅪 ݁ . ⊹ ₊ ݁.

In the XXXth span of the galactic war against the Phoenix King, the Avatar, Master of the Four Elements, summoned his trusted advisor to his side.

“Aang,” said Sokka, the hem of his parka flapping behind, panting little clouds into the frigid air from the jog over.

The Avatar’s customary saffron made him one with the landscape, white painted gold by the slow-setting sun. He turned, grinned wide, and allowed himself to be pulled down into a kunik. “Sokka.” He leaned back to clap Sokka’s shoulder, then tugged him deep into the chambers of the igloo. “Good to see you back in one piece.”

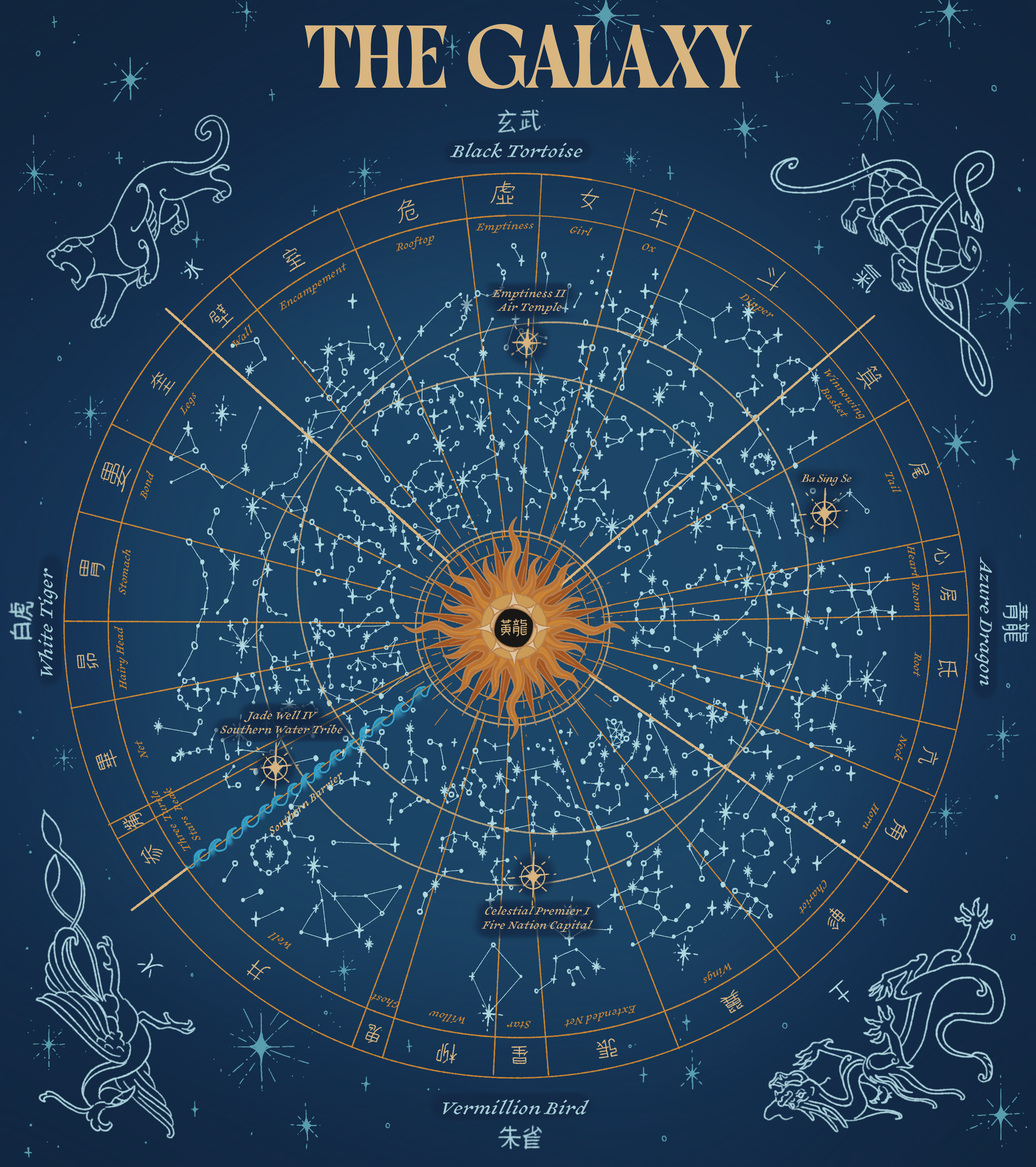

“Good to feel solid ground under my feet again,” said Sokka. That was true: to feel the snow crunch beneath his boots, his gait syncing back to his familiar weight of Jade Well IV after the long patrol along the southern border of the White Tiger of the West. Homecoming, after decades of travel to all corners of the galaxy, was sweet as ever. Every Sokka that had come before him had agreed on that, at least.

Katara was inside, bustling about; she offered him a perfunctory kunik before thundering down one of the hallways, yelling for Sokka’s teenage nephew to pick his clothes off the floor. A kettle was already huffing over the fire, and Aang poured its contents over the waiting tea leaves.

“Good mission?” he asked, wafting the cup over to Sokka on a gust of air when the tea was done.

A formality. Sokka had sent over a detailed radio report before his return, but he sipped obligingly and launched into his recount. “Business as usual. The cohorts there are doing well. It’s been quieter lately, those Fire Nation ships prowling at our doorstep looking for an opening we’ll never give them. Oh, and Bumi says hi.”

Aang’s smile had a rueful edge to it, which he hid behind his teacup. “Ah, all grown up. His last radio was weeks ago.”

“You know how it is out there. They work the recruits hard. Everyone’s got five jobs at once, they’re running him ragged! And he’s a big boy, he doesn’t even wanna be hanging out with his uncle in front of…” He trailed off. “Aww, Aang, I don’t mean it like that.”

“No, no,” said Aang, “it’s not—” He took another sip of his tea. He worried at his sleeve. Then, he said, “I’ve recalled you for a reason. I have a mission for you.”

Sokka sat up. “I’m all ears.”

“As you know, the Phoenix King has been plotting the impossible.”

“Big fan of the impossible, that guy. Anything within the realm of possibility is simply unthinkable for the likes of His Majesty.” Know thine enemy, and Sokka had made a real study of him—as much as he could, with the distance the man had managed to maintain between them all these decades. Megalomaniac, egomaniac, and plain old maniac: let it not be said the Phoenix King did not contain multitudes.

“Sokka.” Aang knew him well enough to let some fondness flash before he became the stern Avatar again. “He’s going to do it. He’s found a way. He’s going to cross the Black Tortoise.”

Sokka narrowed his eyes, set his teacup down. “What have I missed here?”

Aang sighed. “They’re starting to amass at the Winnowing Basket mansion. They’ve been planet-hopping through the colonies dotted through the Earth Kingdom… That’s why it’s been quieter at the border, I suspect.”

“That’s the northernmost mansion of the Azure Dragon,” said Sokka, rubbing his beard. “Shit.” Aang had laid the groundwork, and that was enough for his mind to slot together the rest of it. “He was never going to get across without enough fuel—not to mention those poor fucks they’ve got on the reactors. And that’s not just to blast across the Black Tortoise, but to launch a full invasion of the White Tiger.”

He shivered. The White Tiger of the West, the base of their operations against the Fire Lord but more importantly, their own abode. This was the home of the Water Tribes, northern and southern. Since the reemergence of the Avatar after his century-long disappearance from the galaxy, its southern border had been well-defended, more recently by Sokka himself, against the Phoenix King’s domain of the Vermilion Bird. The northern border was defended by a natural barrier: the Black Tortoise, the former domain of the Air Nomads and Aang’s former home, the expanse that had lain barren since the genocide that lit the flame of war. In that stretch was nary an earthbender to mine uranium for the Fire Nation’s warships, and not a single soul to replace on the reactors when the labourers succumbed to the poison.

“The treaty they signed with the Wei clan in the last span,” said Aang ruefully. “They had a territorial dispute with the Zhangs…”

“...and the Fire Nation troops have been helpfully clearing those Zhangs off the star system.” Katara, having returned, propped a hip against the doorframe. “And they’re not doing it for free.”

“A base of operations,” said Sokka. “Fuel, food, and bodies.”

“Yep.”

“Shit.” Sokka sat back, mind whirring. “There’s no way we can put up a barrier fast enough… the one we have down there took us spans, and who knows if that fuckwit Hahn would take us seriously, again, and if those bastards break through the north then—”

“Sokka—”

“Uncle?” said a young woman’s voice. Sokka’s head snapped up. His niece Kya had shouldered past her mother into the room, dressed in a standard-issue military parka. “Uncle, I want to come with you.”

“Oh for goodness’ sake,” snapped Katara. “You’re not going anywhere.”

“Come where?”

“Uncle, I’m good in a riptide, I’ve done my standard training, my bending’s—”

“This conversation is not for you. Go back to your room, young lady!”

“I’m old enough. I’m older than you were when you and ataata—”

Katara raised a hand. Water pulled out from the ice walls, gathering to swirl in her palm. “Go.”

Kya’s face pinched. She slunk back through the door.

“Sorry,” said Sokka, “where am I going?”

Katara and Aang exchanged a look, the kind you could do when you had been married for decades and were about to throw your brother into a riptide. Oh no.

“Not all is lost,” said Aang. “I have someone I would like to task you to recruit.”

“Alright,” said Sokka. “Who?”

“He lives on my home planet.”

“Sure.” Then, “Wait, your home planet?’

Serenely, Aang said, “Yes.”

“Can you—live there? Can anyone?”

“Well, yes. Yes, one can live quite comfortably there now.”

“N…ow? And you’ve know this for… how long?” Sokka wheeled round to glare at Katara, who merely looked away. “When did you plan on sharing?”

“Many spans ago, I met a rogue traveller during our travels through the galaxy,” said Aang. “He was… purposeless, directionless. A lost soul. So I tasked him with custodianship over my home planet. And since then, he and the refugees have breathed new life into it.”

Something was curdling in Sokka’s gut. “Refugees?”

“Thanks to him, my home turned from a barren wasteland into a sanctuary…”

“Whole spans,” said Sokka. “When were you going to tell me?”

“The Avatar has his reasons,” said Katara, clipped.

“You have to understand, Sokka,” Aang beseeched. “For his safety, I could not tell a soul. Not even our children. The people on that planet depend on secrecy for their survival—”

“Katara knows.”

“Drop it,” snapped Katara. “This is way bigger than you.”

Sokka would’ve quite liked to respond to that, but Aang—ever the diplomat of their partnership—jumped in. “It all rests on you, Sokka. The only souls that know about him are in this room right now. I swear to you. You’re the only one I—we can trust with this. With all your strategic experience, there’s no one better placed to persuade him to join our cause.”

He was a sweet talker alright. But he was also that—sweet—and that was why Sokka loved him as his own brother. So he swallowed down the hard lump that was resentment and let it go uneasy down his gullet. The Avatar’s right hand man. Need the hand be privy to the designs of the mind? “So, who is it? The custodian of your planet.”

“Oh,” said Aang breezily. “The Phoenix King’s son.”

And Sokka, who—it must be said—had made a valiant attempt to calm his simmering emotion, exploded now. “Who?!”

. ݁₊ ⊹ . ݁ 𓅪 ݁ . ⊹ ₊ ݁.

“Knock knock. Anyone here?”

“No,” said Sokka, but Katara barged into the shipyard anyway. Sokka glared, then returned to his tinkering.

“Brought you muktuk.” She held out a package and, when Sokka didn’t take it, left it atop a water drum. And then hovered.

“I’m quite busy, you know,” said Sokka. “Got a trip to the other side of the galaxy coming up? Ring a bell?”

“Oh, come on. You can’t stay angry forever.”

Try me, Sokka thought. Aloud, he said, lightly, “When did we start keeping secrets from each other? Do enlighten me, sister dearest.”

“You know he had no choice,” hissed Katara. “Look, it’s a shame that you—”

“Is the Avatar so lofty he needs delegates to deliver his apologies now?”

“He was sworn to secrecy— If word got out that he was still alive and on that planet, every single person there would suffer the Phoenix King’s wrath.”

“You know.”

“Yes, well.” Katara sniffed. “I’m his wife. Doesn’t that count for something?”

Sokka turned sourly back to his ministrations. That was the crux, wasn’t it? After all these decades together, it was Aang-and-Katara, and then Sokka. He always came second.

“Do you trust him?” He didn’t mean Aang.

“Of course I do,” Katara said. “You think I’d send you on a suicide mission?”

“You’ve sent me on plenty.”

“You’re incorrigible.” Katara smoothed a hand down her parka. “As though Kya hasn’t been giving me enough grief lately.”

“You’re too hard on her,” said Sokka.

“She’s a ch— She’s young.”

Sokka caught the slip; charitably, he thought, he did not comment on it. “She’s nineteen.”

“That’s young.”

“That’s five years older than you were when we found Aang.” Then he changed tack. “Bumi’s been really coming into his own on the frontier.”

“I didn’t ask you for advice on parenting my daughter.”

“But you don’t see her as your daughter, do you?”

Katara said, “Watch your tongue, General.”

Sokka, when he found the sore spot, was accustomed to twisting the knife. His sense of self preservation had never been high; that was why he excelled in his line of work. “Just because she carries our mother’s chip—”

A whistle through the air, a slice of cold against his cheek. A lock of hair fell from his wolf tail to his feet. The ice shard shattered behind him against the hull of his ship. Katara was breathing hard.

“Goodbye, Sokka,” she said. “I wish you safe passage.”

. ݁₊ ⊹ . ݁ 𓅪 ݁ . ⊹ ₊ ݁.

The journey to the galaxy’s shrouded north was long, and lonely.

When his ship finally veered into the Emptiness mansion, he felt only a grim relief. It was a mansion populated by ten star systems; his destination was the star that shared its name, planet unknown. When he turned on his radio, the reply was instantaneous.

“General Sokka,” said a woman’s voice, mellow-deep through the crackle, “we’ve been expecting you. I’ll send you the coordinates.”

Sokka entered them as she read them out: the radio map plotted his course to the second planet in the system. And then he was approaching Emptiness II, an ever-growing dot of light girded by its rings, and veering to dock his ship on the planet’s sole satellite: a moon blasted into a permanent crescent shape. He had grown up knowing about the great supernova that Fire Lord Sozin, the great-grandfather of Aang’s little friend on the planet before him, had harnessed the power of against all four Air Nomad settlements in the Black Tortoise of the North. Who didn’t? The greatest atrocity of their age. But confronted now with the sheer power of the weapon, Sokka shuddered.

It was a rudimentary station; there was no room for Sokka to berth. The voice over the radio shot off more instructions and he dutifully chained his craft to one of the existing ships to stop it from floating off, then bounced out of the airlock.

He was featherlight on the moon, springing footsteps puffing up dust under his boots. He made his way down the line of ships—outdated, motley, but well-maintained—and went up to the ship where the speaker on the radio awaited him.

At the top of the ladder was a view of Aang’s home planet. Sokka stopped to stare.

Below, over the jagged horizon of the shattered moon, it glowed blue—blue with its oceans swollen after Sozin’s sun weapons had melted the icecaps, and after the rhythm of the tides was choked out by the destruction of the moon. And those remnant fragments were dotted in orbit all around the planet like tundra midges in the summer—

“General,” said the woman on the radio drolly, into his earpiece, “plenty of time to look later.”

Sokka chuckled, and it broke over the welling emotion. “Of course, ma’am. Do let me in.”

The airlock slid open. When Sokka stepped inside, his feet readjusted to the artificial weight inside: heavier than the moon, but a hair lighter than what he was used to back home. He pulled his helmet off and took a breath, shaking out his hair.

“General Sokka,” said the woman from the radio. “It is an honour.”

She was standing before him now, bowing. Eyes kohl-lined, hair plaited down her back; Sokka guessed her to be at about fifty spans of age. There was a no-nonsense dignity to the way she carried herself. “What should I call you?”

“This one is Osha, General.”

Osha. A Fire Nation name, if Sokka had guessed correctly. He took out his fan with an affected casualness. “Thanks for welcoming me.”

“I couldn’t miss it. Everyone has been so excited for your arrival. General, you’re a celebrity.”

So the inhabitants on the planet were apprised of the happenings in the world beyond. Sokka filed that tidbit away. “Well, take it away, Osha. Can’t keep my adoring fans waiting.”

He watched the planet near through the sliver of crystal embedded into the shell of Osha’s ship as they approached, its impossible blue. Then a static flash: a ghost-print of the same view but the coastlines all different, eating green into the oceans, big patches of white around the poles. He shook his head and the image melted away. “Emptiness II. That’s a creepy name for a planet.”

“It leans into the philosophy of the Air Nomads,” said Osha. She was sitting behind him, hand on the rudder and eye on the radio map that plotted out the route and environs ahead. “Emptied of desire, to shed the cycle of suffering and reach enlightenment.”

Watching the space debris, Sokka couldn’t help but wonder how much suffering this philosophy had averted. Then Osha hit the radio. “We’re heading through boys, open her up.”

Before his eyes, the orbiting moon-fragments started to shiver, then move. “Hold on tight.”

“Wh—?” said Sokka, already strapped tight into his seat. A gap was opening through the debris. “Earthbenders?”

“Neat, right?” said Osha, though her eyes remained fixed on the radio map. “They get rostered to stand guard at the moon and they open and close our gates.” She waved a finger at the map, no doubt tracing the planetary rings. “But not everything out there is earth, so we still need to be careful.”

An object ahead; small, by the looks of it. Osha pushed the rudder. Sokka saw it pass through the sliver of crystal. “That’s metal,” he said. “The mast, red paint, I’ve never seen this make in person…”

“From a hundred spans ago,” said Osha.

“A Fire Nation battleship.”

“There’s a lot more of the other guys.”

She swerved again. The next piece of space junk was a hull blasted in half, almost neatly. From the small window Sokka saw the string of sun-bleached flags trailing from one mast—something he had only seen in books. “The Air Nomads.”

Osha nodded once; her gaze was fixed predator-like on the radio map’s screen. Another sharp turn and Sokka recoiled when he saw the next piece of debris drift past.

“What was that one?” said Osha, noticing.

“An… arm?”

“Hm.” Her lips pinched. “You do get the occasional one.”

The next object registered larger on the map. Sokka watched the window with some trepidation, and whatever instinct had cautioned him was proven right. First came the spacesuits, lit chiaroscuro by the fierce white light of Emptiness behind them, whole sets spiralling slowly around the pull of the planet below, splayed limbs frozen in rigor mortis. They were the lucky ones. There were suits bisected at the waist by jagged black scorch marks. There were unidentifiable black husks. And then there were the remains that time had separated from their suits, charred and undecomposed for a hundred spans, suspended in perpetual orbit.

“The necropolis,” said Osha, hushed.

Sokka watched the corpses careen past, these scars of a century-old battle hung in diorama over the planet. “Do you ever get used to it?”

“No, never.”

They sailed through, Sokka’s gaze unable to detach from the sight. “General,” said Osha, “atmospheric entry.”

The clipped tone made Sokka start. Military; not just any military, with her name. Ex-Fire Nation military. He pulled his gaze from the window and the corpses, the graveyard left by her ancestors. His grip tightened on the straps of his seat and he plastered a grim smile over his face. “Take us down, Osha.”

. ݁₊ ⊹ . ݁ 𓅪 ݁ . ⊹ ₊ ݁.

The ship landed atop a vast lake in the planet’s southern hemisphere, skimming its surface before coming to rest beside the shore. They shed their spacesuits and Osha helped him out onto the dock; Sokka blinked in the searing white glare of Emptiness above, then pulled a pair of snow goggles over his eyes.

“A glacial lake?” he said, taking in the surroundings. They were high up in altitude, snow-capped mountains shouldering heavenwards on all sides, ice pressing fierce and white into the pristine waters. The shoreline was rocky; strings of multicolour flags fluttered in the chill breeze. It was desolate, lonely; he was galactic miles from home.

“Our waterbenders have done some great restoration around here,” said Osha. She ushered him to a patient creature waiting beside a shack beside the dock. One Sokka was much familiar with: the second sky bison he had ever seen. “You’ll forgive us for the muted reception, General. Everyone’s waiting for you at the temple.”

“You— that’s—” Sokka shook his head. Reset. One thing at a time. “Waterbenders?”

“Yep, some southerners like you, I believe,” said Osha, nudging him into the bison’s saddle. “Your sister instructed them a few times when she visited.”

Right. When she visited. Without his knowledge, over the past twenty-five spans. Sokka made a valiant effort not to brood as the bison took off.

The landscape changed under them, a lexicon of mountains: the cold white alpine heights softening into the treeline, then the plateau. “We regenerated the soil here for agriculture,” said Osha casually as they soared past. “And the rice paddies and tea plantations further down in the foothills.” She gestured to their left, where Sokka could make out the terraces, green striping the hillsides. This was the place where Aang grew up, Sokka realised, over a hundred years ago. Had he flown over these same mountains with Appa? Did the same wind nip cold at his scalp?

“I thought—” said Sokka. “Aang told us the whole planet had died.”

Osha spared him a backwards glance. “It’s true. It was a husk when we came, mass extinction from the warming or just being burned to ashes. The Avatar did a lot of groundwork just fixing up air and ocean currents.”

So pleasant to hear about Aang’s extracurriculars. “You’re raising the sky bison again? Giving Appa some cousins?”

Osha patted the bison’s head and it lowed in such a heartbreakingly familiar way. “Every bison contains a bit of his material,” she said. “We had bones and engineered whole ecosystems back from them, but there’s always something missing.” Something stirred in Sokka’s subconscious—splicing animals together, that was ancient lore, where did that come from?—and then Osha was saying, “Oh hey, General, we’re close!”

The bison swooped downwards. Sokka saw the vista, and it was breathtaking. The mountains rose like spindles from the vegetation below, sheer rock faces and the trees that clung to them. The bison swerved between them and Sokka marvelled as the cliffs rose on either side, the claustrophobia. When they swung around the next bend he saw it rise before them.

What struck him first was the colour, how it heaved with life. It was on everything: the roofs, the painted walls of the village houses, the flags that trimmed the streets, leading all the way up to the temple that perched at the summit. It was a settlement etched into the mountain.

They swooped upon it. Osha landed them in a paddock where other sky bison were chewing hay or taking lazily off into the sky. It was like looking at a field full of Appa clones and little ones too, the juveniles latched onto the mother, huddling beneath the legs or trailing behind her in the sky. But a clamour at knee-height stopped Sokka from following the thread of feeling that bubbled up at the sight. He looked down.

“Is it true you’re the one who killed all those Fire Nation soldiers in the battle?” cried a child, gaps showing between her teeth.

Sokka waggled his eyebrows. “You’ll have to be specific.”

“At the battle of Seat Flags VI in the hundred and first span of Avatar Aang, then the battles of the Well mansion in the hundred and second span, and then the battle of—”

“General Katara’s my favourite,” piped up another.

“My sister?”

“She froze a WHOLE planet, lured the Phoenix King’s army into landing onto an ice planet, and then unfroze it. They all drowned!”

“The ambush of Fish III. That was my idea,” said Sokka, partly proud, partly reasserting his claim in the sibling rivalry. That had been the first planet they’d reconquered of Ba Sing Se.

“Come on now, youngsters,” said Osha, cutting through with an arm around his back, “don’t swamp the General.”

“It’s nostalgic,” said Sokka. “My niece and nephews haven’t done this to me in a decade.”

The children followed them partway up the street, then dropped off back to their kite game. The path wound ever upwards through the heart of the village like a cobbled vein. Pulley systems on either side drew cartons up and down its slope, and Osha laughed as he bent down to inspect the mechanics. Villagers came to greet him, calling him by name or bowing to him. There were so many going about their day, regular folk of all ages garbed in the clothes of—if Sokka were not mistaken—all four nations. Living all together here, in the husk of the Air Nomads’ civilisation.

But before his eyes was no husk. He leapt when flame burst from a villager’s hand but he was only roasting a skewer of meat, and a gaggle of youths cheered and ate it with gusto. Between yellowing leaves flitted a pair of birds, plumage black and white; the sunlight picked out an iridescent shimmer on their tails. A winged lemur, just like Momo, flapped after them. Higher still above them wheeled even greater winged shapes: gliders. And people, non-airbenders, were simply—commuting in them. Something Sokka had only seen Aang (and later Tenzin) do, but out here it looked so… mundane.

The hike took the wind out of Sokka’s lungs; he had to pause to fan himself. “Here’s the centre of it all,” said Osha, who didn’t sound the least bit puffed. “The air temple.”

It reared above them. The gates beckoned. Sokka had heard the stories from Aang: sky bison soaring overhead, the monks freewheeling through their forms, teeth tearing through cream-topped moon peaches as the juice burst upon the tongue. Watching the scene before him, it was as though nothing had changed. Rows of young folk filled the temple courtyard; a drum echoed over the stonework and they changed formation in one swift motion, a bird ruffling its feathers. Osha led them through down the middle. The disciples, Sokka noted, were of mixed gender and ethnicity, ranging from Tenzin’s age to their early twenties. They ranged tall, tall like Aang, owing perhaps to the relative lightness of the planet’s attraction. Somewhere above, someone was playing the flute badly. More drums, and they twirled their staffs in unison, a tide crashing ashore.

Sokka watched pensively, getting a bird’s eye view as they climbed the next set of ramparts up the temple. He leaned over the railing to catch his breath—wooden, painted yolk-yellow—and followed the formations below. Movements precise, strikes sharp. Put them in the field, how would they perform? The drum rumbled and they hurried to split in two. Good discipline, quick to obey. He snapped his fan back open and overlaid it upon the two groups. Like a pair of wings. An outdated form, from a world twenty-five spans out of sync.

“I don’t know where he is,” Osha was saying, flustered, “he told me he’d meet us here at the hour of the monkey, he’s probably—” and then there was a roar of wind.

A banner of red punched through Sokka’s vision. Unending red, sinuous, which blasted across and then twisted up and around: a violent shimmer in the sunlight. The wind buffeted Sokka’s clothes; he heard a passing whoop. He pulled off the snow goggles and winced at the flare of light. The disciples in the courtyard scattered. The huge coil of red landed with a thump and flurry of leaves, then the huge face of a dragon—a dragon! Sokka thought faintly—was peering up at him and puffing smoke up into his face. Sokka coughed and batted it away with his fan. It was the first dragon he had ever seen, weren’t they all meant to be extinct? But no—a volcano rising from a glittering golden sea, the unimaginable heat, oppressive and cleansing both, great wyrms twisting through the clouds above—

Sokka shook the ghost-memory away. Not the time. Absurdly, the poor flautist warbled away. And amid the cloud of white, the dragon rider vaulted off.

“Ugh, interminable show-off,” said Osha, no small amount of fondness in her voice. “General, you must forgive him…” Sokka wasn’t listening. His gaze followed the figure up the stairs, until it disappeared around the bend. The sound of the flute cut short. He moved to look.

He saw the back of the seneschal, garbed in bruised red and the colour of millet. The flautist was a child, sitting with legs drawn up on sacks of rice. The seneschal opened his palm.

The child looked up. The cacophony stopped. The flute went into the open palm. And something flashed in the seneschal’s other hand, in the sunlight. A knife. Sokka started. The seneschal’s body hid his hands, but when he handed the instrument back, the child grinned. When he picked his tune back up with the same unskilled gusto, it was this time distinctly—blessedly—in tune.

The seneschal turned.

Sokka had been briefed on the basic facts. He knew the seneschal’s name was Zuko, that he was about Sokka’s age, that he had been banished by his father at age thirteen, that he had been the steward of Aang’s planet for the last twenty-five spans. But he felt distinctly unprepared when this man, forgotten by time, closed in on him. In his thirty spans of conflict against the Fire Nation, Sokka had never seen the Phoenix King in person, though he had seen the illustrations—including one made of noodles, courtesy of Aang. He had wondered, sometimes, what the man himself might look like in the flesh, liberated from the artist’s stylised brush; wondered too whether the portraits’ aristocratic handsomeness was a vanity, smoothing over a weak chin or crooked nose. But the identifying difference between the Phoenix King’s portraits and the man approaching Sokka now was the large burn scar over one eye, wrapping over to his ear and streaking down over his cheek.

Sokka bowed to hide his surprise, and said, “I am General Sokka of the Southern Water Tribe, hailing from Jade Well IV. I send my greetings—”

“From the Avatar?” said Zuko. And he was coming close, closer, closing in, and he clasped Sokka’s forearm. The Southern Water Tribe greeting. “Any friend of Aang is a friend of mine.”

. ݁₊ ⊹ . ݁ 𓅪 ݁ . ⊹ ₊ ݁.

The custodian of the planet ushered Sokka inside. He wended through the temple, its interiors draped in light and colour—flags, flowers, frescoes. He turned prayer wheels with an idle hand as he passed, helped a teenager right a stack of tilting steamers, whispered a move to a pai sho player while the other wailed at him in mock dismay. Sokka tried to keep pace. But the relative lightness of the planet and his cybernetic knee were no match for the endless stairs looping their way up the temple.

“You don’t go easy on the stairs here, huh?” Sokka huffed.

Half a flight up, Zuko deigned to offer him a half-turn. A smile played at his mouth. “We’re all used to it. Most of us get around with gliders, or the flying beasts. But there’s a goods lift we could crack out for you?”

Sokka was a decorated general, a veteran of thirty spans in the arena of war. “I’ll give it a pass.”

Zuko led him to a room on the highest floor and stepped aside to let him enter first. It was airy, panelled with dark wood. A low seating platform dominated the centre, which Zuko ushered him towards. Sokka, sweating a little, took off his parka and eased himself onto a cushion.

When Zuko lit the fire under the teapot, Sokka jumped. The spark that burst from his open palm flared bright, then allowed itself to be stuffed into the brazier.

“Sorry about that,” said Zuko. He was watching Sokka. “Just reheating. I didn’t even think…”

“It’s fine,” said Sokka. He thought, unerringly, of the necropolis around the planet. An orbit of charred limbs. “Don’t worry. Just—” Just what? Habit? Trauma? Sorry man, I just haven’t seen firebending used outside of mass murder before?

“Um.” Zuko pushed a plate of small cakes towards him. The tips of his fingers were stained with henna, red. “Snack?”

Sokka watched him while he nibbled on the cake—mung bean, soft between his teeth, a muted sweetness. “How’s Aang?” he was saying. “Katara? The kids?”

He was smiling. That was one thing the Phoenix King’s portraits never did, but Zuko had lines pressed around his mouth from it. Threads of grey wove into his topknot and his neat, trimmed beard. When Sokka met his gaze, his eyes wanted to dart away by instinct.

“Doing well,” said Sokka. “Aang’s busy, as usual. Katara’s… a menace, bad news for the Fire Nation. Kids are… well, they’re not really kids anymore. I don’t know how much you know.”

“I’ve always wanted to meet you,” said Zuko.

Sokka said, “The privilege is mine to meet such an… honoured friend of the Avatar.”

“I’ve heard about your exploits, of course.” Zuko took a cake of his own. “Teo’s a whiz with the radio. I was getting blow by blow accounts of your victories at the Southern border.”

Sokka chuckled, took another bite. “I do regret we’d not made our acquaintance earlier.”

“You must understand, the secrecy was crucial.”

“If I am to understand, this restoration was your work.”

The seneschal ducked his head. “I could not have done anything without my community.”

It was hard to get a gauge on him. Zuko busied himself with the teapot as it started to steam. Where did his loyalties lie? A firebender with the Phoenix King’s face, who smiled and rode a dragon. Sokka tapped his fingers against the tabletop when Zuko filled his shallow cup with a pale, opaque liquid.

“Butter tea,” said Zuko. “Just like the airbenders used to drink. We harvest the bison milk.” Sokka took a sip. “What do you think?”

It was nice. Creamy, a little savoury: not a flavour profile Sokka had ever expected from tea. “It’s… different from what we drink at home. We make it out of rhododendron. No milk.”

“We cultivate the tea at the foothills,” said Zuko, taking a sip, “and process it ourselves. This one is fermented, with quite an earthy flavour.”

“A tea connoisseur?”

“I couldn’t possibly claim to be.”

Sokka took another sip. “There’s this dinky teashop in the planet system of Ba Sing Se. The guy who runs it…” He looked up. “But I don’t suppose you’ve ever been.”

“No. I don’t suppose so.” Zuko sipped his tea, refilled Sokka’s cup, and set the teapot down with a clunk. “I assume,” he said, and his voice now was all business, “if the Avatar sent you, this is not a social call.”

The cup hovered at Sokka’s lips. Then he put it down, directly in front of himself.

“This is my people. The Southern Water Tribe.” He took the teapot and put it to his right—south, by the compass. “And this is your—the Phoenix King. For the past decade or so, the White Tiger of the West has been impenetrable from attack from the Vermilion Bird of the South.”

“The ice barrier,” said Zuko.

“My brainchild, my sister’s execution. Daggers of ice arrayed to block the ships’ navigation. It’s repelled every Fire Nation ship that’s tried to get through. The arena of war has largely focused on the Azure Dragon of the East.” Directly opposite his own teacup, Sokka pushed the plate of cakes in place. “The Earth Kingdom, with its myriad settlements.”

“And colonies,” said Zuko.

“This means the only route left for the Fire Nation into the White Tiger is through the Azure Dragon, and the Black Tortoise of the North, empty of its Air Nomads”—Sokka traced with a finger, drawing the arc up around his rudimentary map—“before they hit the Northern Water Tribe.

“The North’s defences are… inadequate.” Sokka felt his lip curl, but this was hardly the time to hash out the long disagreement between himself and Chief Hahn. “You’ll know they haven’t been active in the war—I guess they’ve had little reason to be since the invasion we thwarted, oh, decades ago. But once they fall,” he waggled his own teacup, letting the dregs of tea slosh within, “the Fire Nation will be right at our doorstep.

“Without proximity to resources,” said Zuko, tracing the loop of tea paraphernalia, “an impossible route. Almost a full revolution of the galaxy.”

“Not anymore.” Sokka tapped the cakes. “There are enough colonies in the Azure Dragon now to supply the Phoenix King’s forces across the long trek through the north.” He swept his fingers over the empty expanse of table that lay between the cakes and his own teacup. “That’s where you come in.”

A stricken look was dawning upon Zuko’s features. “Me?”

Sokka snagged Zuko’s cup, its tea abandoned halfway. He put it in that emptiness. “And this is you. Emptiness II. The sole inhabited planet in the Black Tortoise of the North.”

“You want me to join the war,” said Zuko.

He sat up straight. Gone was the easy smile, and the solemnity that replaced it did make him look more like his father’s portraits. “Yes,” said Sokka, simply.

Zuko’s henna-dipped fingers drifted over the array on the table. “I have fifty thousand on this planet,” he said. “Refugees, defectors, people with nowhere else to go. People who escaped the war.”

“Yes.”

“You want me to lead them into war, and against my father.”

“To staunch the escalation of war. To cut off their route to the West, and the devastation he might wreak there.”

“We have shrouded ourselves from war, with no intention of joining.”

“The youths I saw in the courtyard,” said Sokka, taking an idle sip from his teacup. The last drops had gone cold in the shallow cup. “What are they training for?”

“Fitness,” said Zuko. “Mental discipline.”

Zuko held his gaze; the proud line of his features was, Sokka thought, unmistakably aristocratic. Then he retrieved his teacup and drained it. When he set it down again, his face was serene again. “You understand I will have to think on this,” he said. “In the meantime, let me show you your rooms. Get you settled and feeling at home.”