Chapter 1: The Avatar's Home

Chapter Text

. ݁₊ ⊹ . ݁ 𓅪 ݁ . ⊹ ₊ ݁.

And so the star-sisters shed their dove-wings by the pool and dipped into it as women. The Cowherd, desiring them, stole one’s garb. That celestial weaver of cloud-floss became his wife; and her keeper, bereft of her sunset-polychrome cloth, stole the weaver back to the heavens. This cruel mistress stranded husband and wife on opposite banks of the Silver River that glimmered to life at night. But there too was the mercy of magpies when, once a year, those beating wings would span the River and bridge the lovers so they would no longer be kept apart.

. ݁₊ ⊹ . ݁ 𓅪 ݁ . ⊹ ₊ ݁.

In the XXXth span of the galactic war against the Phoenix King, the Avatar, Master of the Four Elements, summoned his trusted advisor to his side.

“Aang,” said Sokka, the hem of his parka flapping behind, panting little clouds into the frigid air from the jog over.

The Avatar’s customary saffron made him one with the landscape, white painted gold by the slow-setting sun. He turned, grinned wide, and allowed himself to be pulled down into a kunik. “Sokka.” He leaned back to clap Sokka’s shoulder, then tugged him deep into the chambers of the igloo. “Good to see you back in one piece.”

“Good to feel solid ground under my feet again,” said Sokka. That was true: to feel the snow crunch beneath his boots, his gait syncing back to his familiar weight of Jade Well IV after the long patrol along the southern border of the White Tiger of the West. Homecoming, after decades of travel to all corners of the galaxy, was sweet as ever. Every Sokka that had come before him had agreed on that, at least.

Katara was inside, bustling about; she offered him a perfunctory kunik before thundering down one of the hallways, yelling for Sokka’s teenage nephew to pick his clothes off the floor. A kettle was already huffing over the fire, and Aang poured its contents over the waiting tea leaves.

“Good mission?” he asked, wafting the cup over to Sokka on a gust of air when the tea was done.

A formality. Sokka had sent over a detailed radio report before his return, but he sipped obligingly and launched into his recount. “Business as usual. The cohorts there are doing well. It’s been quieter lately, those Fire Nation ships prowling at our doorstep looking for an opening we’ll never give them. Oh, and Bumi says hi.”

Aang’s smile had a rueful edge to it, which he hid behind his teacup. “Ah, all grown up. His last radio was weeks ago.”

“You know how it is out there. They work the recruits hard. Everyone’s got five jobs at once, they’re running him ragged! And he’s a big boy, he doesn’t even wanna be hanging out with his uncle in front of…” He trailed off. “Aww, Aang, I don’t mean it like that.”

“No, no,” said Aang, “it’s not—” He took another sip of his tea. He worried at his sleeve. Then, he said, “I’ve recalled you for a reason. I have a mission for you.”

Sokka sat up. “I’m all ears.”

“As you know, the Phoenix King has been plotting the impossible.”

“Big fan of the impossible, that guy. Anything within the realm of possibility is simply unthinkable for the likes of His Majesty.” Know thine enemy, and Sokka had made a real study of him—as much as he could, with the distance the man had managed to maintain between them all these decades. Megalomaniac, egomaniac, and plain old maniac: let it not be said the Phoenix King did not contain multitudes.

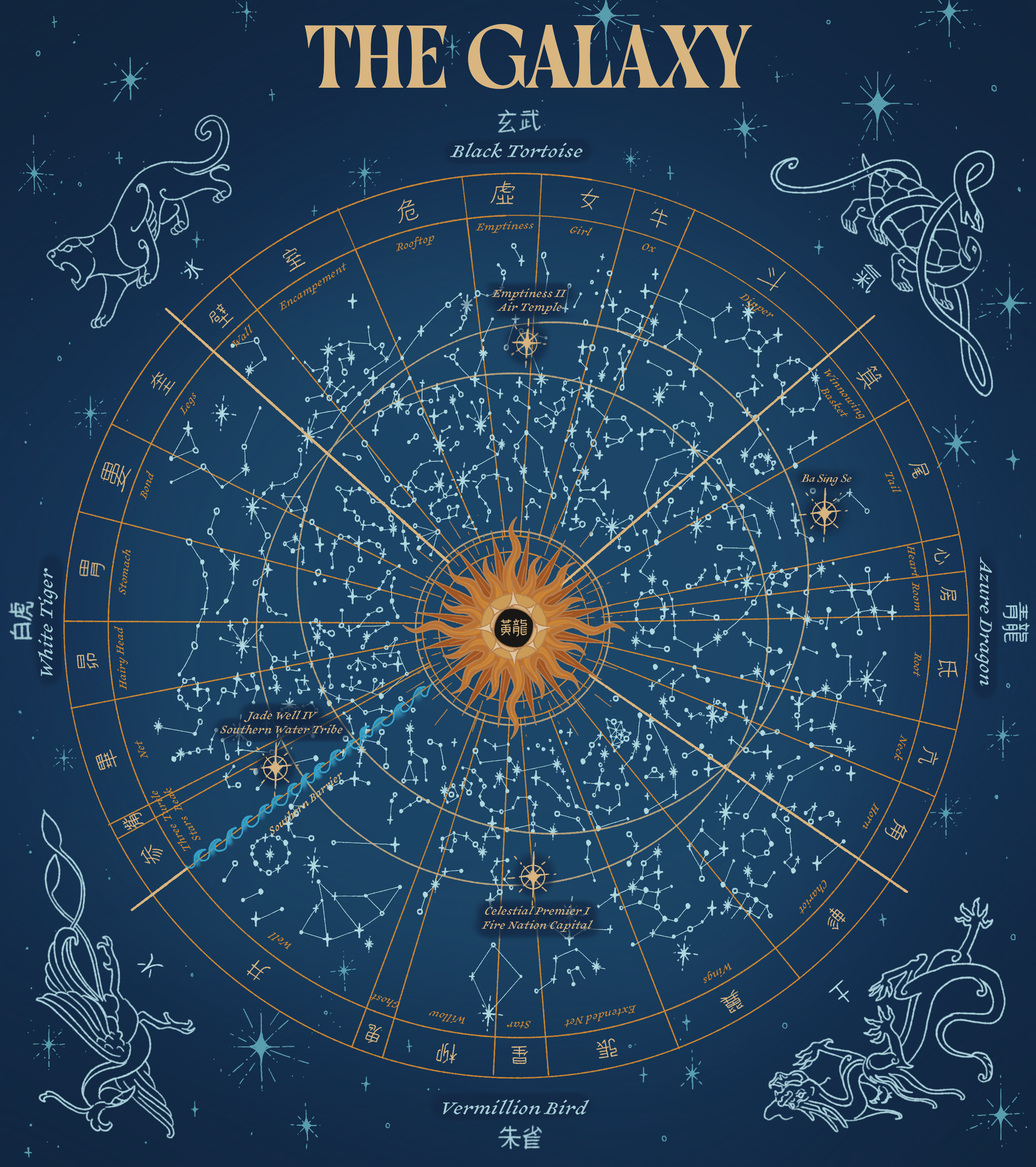

“Sokka.” Aang knew him well enough to let some fondness flash before he became the stern Avatar again. “He’s going to do it. He’s found a way. He’s going to cross the Black Tortoise.”

Sokka narrowed his eyes, set his teacup down. “What have I missed here?”

Aang sighed. “They’re starting to amass at the Winnowing Basket mansion. They’ve been planet-hopping through the colonies dotted through the Earth Kingdom… That’s why it’s been quieter at the border, I suspect.”

“That’s the northernmost mansion of the Azure Dragon,” said Sokka, rubbing his beard. “Shit.” Aang had laid the groundwork, and that was enough for his mind to slot together the rest of it. “He was never going to get across without enough fuel—not to mention those poor fucks they’ve got on the reactors. And that’s not just to blast across the Black Tortoise, but to launch a full invasion of the White Tiger.”

He shivered. The White Tiger of the West, the base of their operations against the Fire Lord but more importantly, their own abode. This was the home of the Water Tribes, northern and southern. Since the reemergence of the Avatar after his century-long disappearance from the galaxy, its southern border had been well-defended, more recently by Sokka himself, against the Phoenix King’s domain of the Vermilion Bird. The northern border was defended by a natural barrier: the Black Tortoise, the former domain of the Air Nomads and Aang’s former home, the expanse that had lain barren since the genocide that lit the flame of war. In that stretch was nary an earthbender to mine uranium for the Fire Nation’s warships, and not a single soul to replace on the reactors when the labourers succumbed to the poison.

“The treaty they signed with the Wei clan in the last span,” said Aang ruefully. “They had a territorial dispute with the Zhangs…”

“...and the Fire Nation troops have been helpfully clearing those Zhangs off the star system.” Katara, having returned, propped a hip against the doorframe. “And they’re not doing it for free.”

“A base of operations,” said Sokka. “Fuel, food, and bodies.”

“Yep.”

“Shit.” Sokka sat back, mind whirring. “There’s no way we can put up a barrier fast enough… the one we have down there took us spans, and who knows if that fuckwit Hahn would take us seriously, again, and if those bastards break through the north then—”

“Sokka—”

“Uncle?” said a young woman’s voice. Sokka’s head snapped up. His niece Kya had shouldered past her mother into the room, dressed in a standard-issue military parka. “Uncle, I want to come with you.”

“Oh for goodness’ sake,” snapped Katara. “You’re not going anywhere.”

“Come where?”

“Uncle, I’m good in a riptide, I’ve done my standard training, my bending’s—”

“This conversation is not for you. Go back to your room, young lady!”

“I’m old enough. I’m older than you were when you and ataata—”

Katara raised a hand. Water pulled out from the ice walls, gathering to swirl in her palm. “Go.”

Kya’s face pinched. She slunk back through the door.

“Sorry,” said Sokka, “where am I going?”

Katara and Aang exchanged a look, the kind you could do when you had been married for decades and were about to throw your brother into a riptide. Oh no.

“Not all is lost,” said Aang. “I have someone I would like to task you to recruit.”

“Alright,” said Sokka. “Who?”

“He lives on my home planet.”

“Sure.” Then, “Wait, your home planet?’

Serenely, Aang said, “Yes.”

“Can you—live there? Can anyone?”

“Well, yes. Yes, one can live quite comfortably there now.”

“N…ow? And you’ve know this for… how long?” Sokka wheeled round to glare at Katara, who merely looked away. “When did you plan on sharing?”

“Many spans ago, I met a rogue traveller during our travels through the galaxy,” said Aang. “He was… purposeless, directionless. A lost soul. So I tasked him with custodianship over my home planet. And since then, he and the refugees have breathed new life into it.”

Something was curdling in Sokka’s gut. “Refugees?”

“Thanks to him, my home turned from a barren wasteland into a sanctuary…”

“Whole spans,” said Sokka. “When were you going to tell me?”

“The Avatar has his reasons,” said Katara, clipped.

“You have to understand, Sokka,” Aang beseeched. “For his safety, I could not tell a soul. Not even our children. The people on that planet depend on secrecy for their survival—”

“Katara knows.”

“Drop it,” snapped Katara. “This is way bigger than you.”

Sokka would’ve quite liked to respond to that, but Aang—ever the diplomat of their partnership—jumped in. “It all rests on you, Sokka. The only souls that know about him are in this room right now. I swear to you. You’re the only one I—we can trust with this. With all your strategic experience, there’s no one better placed to persuade him to join our cause.”

He was a sweet talker alright. But he was also that—sweet—and that was why Sokka loved him as his own brother. So he swallowed down the hard lump that was resentment and let it go uneasy down his gullet. The Avatar’s right hand man. Need the hand be privy to the designs of the mind? “So, who is it? The custodian of your planet.”

“Oh,” said Aang breezily. “The Phoenix King’s son.”

And Sokka, who—it must be said—had made a valiant attempt to calm his simmering emotion, exploded now. “Who?!”

. ݁₊ ⊹ . ݁ 𓅪 ݁ . ⊹ ₊ ݁.

“Knock knock. Anyone here?”

“No,” said Sokka, but Katara barged into the shipyard anyway. Sokka glared, then returned to his tinkering.

“Brought you muktuk.” She held out a package and, when Sokka didn’t take it, left it atop a water drum. And then hovered.

“I’m quite busy, you know,” said Sokka. “Got a trip to the other side of the galaxy coming up? Ring a bell?”

“Oh, come on. You can’t stay angry forever.”

Try me, Sokka thought. Aloud, he said, lightly, “When did we start keeping secrets from each other? Do enlighten me, sister dearest.”

“You know he had no choice,” hissed Katara. “Look, it’s a shame that you—”

“Is the Avatar so lofty he needs delegates to deliver his apologies now?”

“He was sworn to secrecy— If word got out that he was still alive and on that planet, every single person there would suffer the Phoenix King’s wrath.”

“You know.”

“Yes, well.” Katara sniffed. “I’m his wife. Doesn’t that count for something?”

Sokka turned sourly back to his ministrations. That was the crux, wasn’t it? After all these decades together, it was Aang-and-Katara, and then Sokka. He always came second.

“Do you trust him?” He didn’t mean Aang.

“Of course I do,” Katara said. “You think I’d send you on a suicide mission?”

“You’ve sent me on plenty.”

“You’re incorrigible.” Katara smoothed a hand down her parka. “As though Kya hasn’t been giving me enough grief lately.”

“You’re too hard on her,” said Sokka.

“She’s a ch— She’s young.”

Sokka caught the slip; charitably, he thought, he did not comment on it. “She’s nineteen.”

“That’s young.”

“That’s five years older than you were when we found Aang.” Then he changed tack. “Bumi’s been really coming into his own on the frontier.”

“I didn’t ask you for advice on parenting my daughter.”

“But you don’t see her as your daughter, do you?”

Katara said, “Watch your tongue, General.”

Sokka, when he found the sore spot, was accustomed to twisting the knife. His sense of self preservation had never been high; that was why he excelled in his line of work. “Just because she carries our mother’s chip—”

A whistle through the air, a slice of cold against his cheek. A lock of hair fell from his wolf tail to his feet. The ice shard shattered behind him against the hull of his ship. Katara was breathing hard.

“Goodbye, Sokka,” she said. “I wish you safe passage.”

. ݁₊ ⊹ . ݁ 𓅪 ݁ . ⊹ ₊ ݁.

The journey to the galaxy’s shrouded north was long, and lonely.

When his ship finally veered into the Emptiness mansion, he felt only a grim relief. It was a mansion populated by ten star systems; his destination was the star that shared its name, planet unknown. When he turned on his radio, the reply was instantaneous.

“General Sokka,” said a woman’s voice, mellow-deep through the crackle, “we’ve been expecting you. I’ll send you the coordinates.”

Sokka entered them as she read them out: the radio map plotted his course to the second planet in the system. And then he was approaching Emptiness II, an ever-growing dot of light girded by its rings, and veering to dock his ship on the planet’s sole satellite: a moon blasted into a permanent crescent shape. He had grown up knowing about the great supernova that Fire Lord Sozin, the great-grandfather of Aang’s little friend on the planet before him, had harnessed the power of against all four Air Nomad settlements in the Black Tortoise of the North. Who didn’t? The greatest atrocity of their age. But confronted now with the sheer power of the weapon, Sokka shuddered.

It was a rudimentary station; there was no room for Sokka to berth. The voice over the radio shot off more instructions and he dutifully chained his craft to one of the existing ships to stop it from floating off, then bounced out of the airlock.

He was featherlight on the moon, springing footsteps puffing up dust under his boots. He made his way down the line of ships—outdated, motley, but well-maintained—and went up to the ship where the speaker on the radio awaited him.

At the top of the ladder was a view of Aang’s home planet. Sokka stopped to stare.

Below, over the jagged horizon of the shattered moon, it glowed blue—blue with its oceans swollen after Sozin’s sun weapons had melted the icecaps, and after the rhythm of the tides was choked out by the destruction of the moon. And those remnant fragments were dotted in orbit all around the planet like tundra midges in the summer—

“General,” said the woman on the radio drolly, into his earpiece, “plenty of time to look later.”

Sokka chuckled, and it broke over the welling emotion. “Of course, ma’am. Do let me in.”

The airlock slid open. When Sokka stepped inside, his feet readjusted to the artificial weight inside: heavier than the moon, but a hair lighter than what he was used to back home. He pulled his helmet off and took a breath, shaking out his hair.

“General Sokka,” said the woman from the radio. “It is an honour.”

She was standing before him now, bowing. Eyes kohl-lined, hair plaited down her back; Sokka guessed her to be at about fifty spans of age. There was a no-nonsense dignity to the way she carried herself. “What should I call you?”

“This one is Osha, General.”

Osha. A Fire Nation name, if Sokka had guessed correctly. He took out his fan with an affected casualness. “Thanks for welcoming me.”

“I couldn’t miss it. Everyone has been so excited for your arrival. General, you’re a celebrity.”

So the inhabitants on the planet were apprised of the happenings in the world beyond. Sokka filed that tidbit away. “Well, take it away, Osha. Can’t keep my adoring fans waiting.”

He watched the planet near through the sliver of crystal embedded into the shell of Osha’s ship as they approached, its impossible blue. Then a static flash: a ghost-print of the same view but the coastlines all different, eating green into the oceans, big patches of white around the poles. He shook his head and the image melted away. “Emptiness II. That’s a creepy name for a planet.”

“It leans into the philosophy of the Air Nomads,” said Osha. She was sitting behind him, hand on the rudder and eye on the radio map that plotted out the route and environs ahead. “Emptied of desire, to shed the cycle of suffering and reach enlightenment.”

Watching the space debris, Sokka couldn’t help but wonder how much suffering this philosophy had averted. Then Osha hit the radio. “We’re heading through boys, open her up.”

Before his eyes, the orbiting moon-fragments started to shiver, then move. “Hold on tight.”

“Wh—?” said Sokka, already strapped tight into his seat. A gap was opening through the debris. “Earthbenders?”

“Neat, right?” said Osha, though her eyes remained fixed on the radio map. “They get rostered to stand guard at the moon and they open and close our gates.” She waved a finger at the map, no doubt tracing the planetary rings. “But not everything out there is earth, so we still need to be careful.”

An object ahead; small, by the looks of it. Osha pushed the rudder. Sokka saw it pass through the sliver of crystal. “That’s metal,” he said. “The mast, red paint, I’ve never seen this make in person…”

“From a hundred spans ago,” said Osha.

“A Fire Nation battleship.”

“There’s a lot more of the other guys.”

She swerved again. The next piece of space junk was a hull blasted in half, almost neatly. From the small window Sokka saw the string of sun-bleached flags trailing from one mast—something he had only seen in books. “The Air Nomads.”

Osha nodded once; her gaze was fixed predator-like on the radio map’s screen. Another sharp turn and Sokka recoiled when he saw the next piece of debris drift past.

“What was that one?” said Osha, noticing.

“An… arm?”

“Hm.” Her lips pinched. “You do get the occasional one.”

The next object registered larger on the map. Sokka watched the window with some trepidation, and whatever instinct had cautioned him was proven right. First came the spacesuits, lit chiaroscuro by the fierce white light of Emptiness behind them, whole sets spiralling slowly around the pull of the planet below, splayed limbs frozen in rigor mortis. They were the lucky ones. There were suits bisected at the waist by jagged black scorch marks. There were unidentifiable black husks. And then there were the remains that time had separated from their suits, charred and undecomposed for a hundred spans, suspended in perpetual orbit.

“The necropolis,” said Osha, hushed.

Sokka watched the corpses careen past, these scars of a century-old battle hung in diorama over the planet. “Do you ever get used to it?”

“No, never.”

They sailed through, Sokka’s gaze unable to detach from the sight. “General,” said Osha, “atmospheric entry.”

The clipped tone made Sokka start. Military; not just any military, with her name. Ex-Fire Nation military. He pulled his gaze from the window and the corpses, the graveyard left by her ancestors. His grip tightened on the straps of his seat and he plastered a grim smile over his face. “Take us down, Osha.”

. ݁₊ ⊹ . ݁ 𓅪 ݁ . ⊹ ₊ ݁.

The ship landed atop a vast lake in the planet’s southern hemisphere, skimming its surface before coming to rest beside the shore. They shed their spacesuits and Osha helped him out onto the dock; Sokka blinked in the searing white glare of Emptiness above, then pulled a pair of snow goggles over his eyes.

“A glacial lake?” he said, taking in the surroundings. They were high up in altitude, snow-capped mountains shouldering heavenwards on all sides, ice pressing fierce and white into the pristine waters. The shoreline was rocky; strings of multicolour flags fluttered in the chill breeze. It was desolate, lonely; he was galactic miles from home.

“Our waterbenders have done some great restoration around here,” said Osha. She ushered him to a patient creature waiting beside a shack beside the dock. One Sokka was much familiar with: the second sky bison he had ever seen. “You’ll forgive us for the muted reception, General. Everyone’s waiting for you at the temple.”

“You— that’s—” Sokka shook his head. Reset. One thing at a time. “Waterbenders?”

“Yep, some southerners like you, I believe,” said Osha, nudging him into the bison’s saddle. “Your sister instructed them a few times when she visited.”

Right. When she visited. Without his knowledge, over the past twenty-five spans. Sokka made a valiant effort not to brood as the bison took off.

The landscape changed under them, a lexicon of mountains: the cold white alpine heights softening into the treeline, then the plateau. “We regenerated the soil here for agriculture,” said Osha casually as they soared past. “And the rice paddies and tea plantations further down in the foothills.” She gestured to their left, where Sokka could make out the terraces, green striping the hillsides. This was the place where Aang grew up, Sokka realised, over a hundred years ago. Had he flown over these same mountains with Appa? Did the same wind nip cold at his scalp?

“I thought—” said Sokka. “Aang told us the whole planet had died.”

Osha spared him a backwards glance. “It’s true. It was a husk when we came, mass extinction from the warming or just being burned to ashes. The Avatar did a lot of groundwork just fixing up air and ocean currents.”

So pleasant to hear about Aang’s extracurriculars. “You’re raising the sky bison again? Giving Appa some cousins?”

Osha patted the bison’s head and it lowed in such a heartbreakingly familiar way. “Every bison contains a bit of his material,” she said. “We had bones and engineered whole ecosystems back from them, but there’s always something missing.” Something stirred in Sokka’s subconscious—splicing animals together, that was ancient lore, where did that come from?—and then Osha was saying, “Oh hey, General, we’re close!”

The bison swooped downwards. Sokka saw the vista, and it was breathtaking. The mountains rose like spindles from the vegetation below, sheer rock faces and the trees that clung to them. The bison swerved between them and Sokka marvelled as the cliffs rose on either side, the claustrophobia. When they swung around the next bend he saw it rise before them.

What struck him first was the colour, how it heaved with life. It was on everything: the roofs, the painted walls of the village houses, the flags that trimmed the streets, leading all the way up to the temple that perched at the summit. It was a settlement etched into the mountain.

They swooped upon it. Osha landed them in a paddock where other sky bison were chewing hay or taking lazily off into the sky. It was like looking at a field full of Appa clones and little ones too, the juveniles latched onto the mother, huddling beneath the legs or trailing behind her in the sky. But a clamour at knee-height stopped Sokka from following the thread of feeling that bubbled up at the sight. He looked down.

“Is it true you’re the one who killed all those Fire Nation soldiers in the battle?” cried a child, gaps showing between her teeth.

Sokka waggled his eyebrows. “You’ll have to be specific.”

“At the battle of Seat Flags VI in the hundred and first span of Avatar Aang, then the battles of the Well mansion in the hundred and second span, and then the battle of—”

“General Katara’s my favourite,” piped up another.

“My sister?”

“She froze a WHOLE planet, lured the Phoenix King’s army into landing onto an ice planet, and then unfroze it. They all drowned!”

“The ambush of Fish III. That was my idea,” said Sokka, partly proud, partly reasserting his claim in the sibling rivalry. That had been the first planet they’d reconquered of Ba Sing Se.

“Come on now, youngsters,” said Osha, cutting through with an arm around his back, “don’t swamp the General.”

“It’s nostalgic,” said Sokka. “My niece and nephews haven’t done this to me in a decade.”

The children followed them partway up the street, then dropped off back to their kite game. The path wound ever upwards through the heart of the village like a cobbled vein. Pulley systems on either side drew cartons up and down its slope, and Osha laughed as he bent down to inspect the mechanics. Villagers came to greet him, calling him by name or bowing to him. There were so many going about their day, regular folk of all ages garbed in the clothes of—if Sokka were not mistaken—all four nations. Living all together here, in the husk of the Air Nomads’ civilisation.

But before his eyes was no husk. He leapt when flame burst from a villager’s hand but he was only roasting a skewer of meat, and a gaggle of youths cheered and ate it with gusto. Between yellowing leaves flitted a pair of birds, plumage black and white; the sunlight picked out an iridescent shimmer on their tails. A winged lemur, just like Momo, flapped after them. Higher still above them wheeled even greater winged shapes: gliders. And people, non-airbenders, were simply—commuting in them. Something Sokka had only seen Aang (and later Tenzin) do, but out here it looked so… mundane.

The hike took the wind out of Sokka’s lungs; he had to pause to fan himself. “Here’s the centre of it all,” said Osha, who didn’t sound the least bit puffed. “The air temple.”

It reared above them. The gates beckoned. Sokka had heard the stories from Aang: sky bison soaring overhead, the monks freewheeling through their forms, teeth tearing through cream-topped moon peaches as the juice burst upon the tongue. Watching the scene before him, it was as though nothing had changed. Rows of young folk filled the temple courtyard; a drum echoed over the stonework and they changed formation in one swift motion, a bird ruffling its feathers. Osha led them through down the middle. The disciples, Sokka noted, were of mixed gender and ethnicity, ranging from Tenzin’s age to their early twenties. They ranged tall, tall like Aang, owing perhaps to the relative lightness of the planet’s attraction. Somewhere above, someone was playing the flute badly. More drums, and they twirled their staffs in unison, a tide crashing ashore.

Sokka watched pensively, getting a bird’s eye view as they climbed the next set of ramparts up the temple. He leaned over the railing to catch his breath—wooden, painted yolk-yellow—and followed the formations below. Movements precise, strikes sharp. Put them in the field, how would they perform? The drum rumbled and they hurried to split in two. Good discipline, quick to obey. He snapped his fan back open and overlaid it upon the two groups. Like a pair of wings. An outdated form, from a world twenty-five spans out of sync.

“I don’t know where he is,” Osha was saying, flustered, “he told me he’d meet us here at the hour of the monkey, he’s probably—” and then there was a roar of wind.

A banner of red punched through Sokka’s vision. Unending red, sinuous, which blasted across and then twisted up and around: a violent shimmer in the sunlight. The wind buffeted Sokka’s clothes; he heard a passing whoop. He pulled off the snow goggles and winced at the flare of light. The disciples in the courtyard scattered. The huge coil of red landed with a thump and flurry of leaves, then the huge face of a dragon—a dragon! Sokka thought faintly—was peering up at him and puffing smoke up into his face. Sokka coughed and batted it away with his fan. It was the first dragon he had ever seen, weren’t they all meant to be extinct? But no—a volcano rising from a glittering golden sea, the unimaginable heat, oppressive and cleansing both, great wyrms twisting through the clouds above—

Sokka shook the ghost-memory away. Not the time. Absurdly, the poor flautist warbled away. And amid the cloud of white, the dragon rider vaulted off.

“Ugh, interminable show-off,” said Osha, no small amount of fondness in her voice. “General, you must forgive him…” Sokka wasn’t listening. His gaze followed the figure up the stairs, until it disappeared around the bend. The sound of the flute cut short. He moved to look.

He saw the back of the seneschal, garbed in bruised red and the colour of millet. The flautist was a child, sitting with legs drawn up on sacks of rice. The seneschal opened his palm.

The child looked up. The cacophony stopped. The flute went into the open palm. And something flashed in the seneschal’s other hand, in the sunlight. A knife. Sokka started. The seneschal’s body hid his hands, but when he handed the instrument back, the child grinned. When he picked his tune back up with the same unskilled gusto, it was this time distinctly—blessedly—in tune.

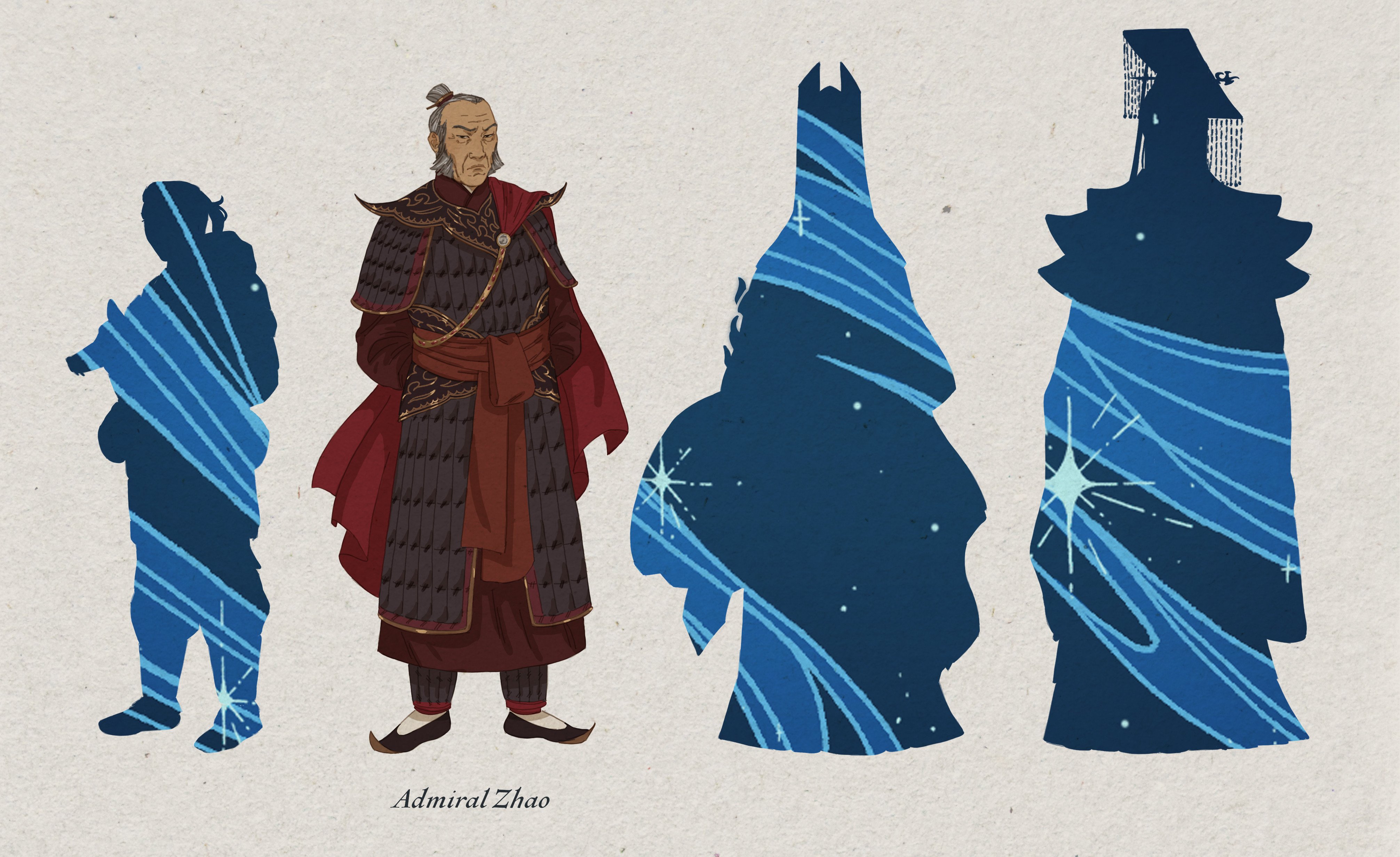

The seneschal turned.

Sokka had been briefed on the basic facts. He knew the seneschal’s name was Zuko, that he was about Sokka’s age, that he had been banished by his father at age thirteen, that he had been the steward of Aang’s planet for the last twenty-five spans. But he felt distinctly unprepared when this man, forgotten by time, closed in on him. In his thirty spans of conflict against the Fire Nation, Sokka had never seen the Phoenix King in person, though he had seen the illustrations—including one made of noodles, courtesy of Aang. He had wondered, sometimes, what the man himself might look like in the flesh, liberated from the artist’s stylised brush; wondered too whether the portraits’ aristocratic handsomeness was a vanity, smoothing over a weak chin or crooked nose. But the identifying difference between the Phoenix King’s portraits and the man approaching Sokka now was the large burn scar over one eye, wrapping over to his ear and streaking down over his cheek.

Sokka bowed to hide his surprise, and said, “I am General Sokka of the Southern Water Tribe, hailing from Jade Well IV. I send my greetings—”

“From the Avatar?” said Zuko. And he was coming close, closer, closing in, and he clasped Sokka’s forearm. The Southern Water Tribe greeting. “Any friend of Aang is a friend of mine.”

. ݁₊ ⊹ . ݁ 𓅪 ݁ . ⊹ ₊ ݁.

The custodian of the planet ushered Sokka inside. He wended through the temple, its interiors draped in light and colour—flags, flowers, frescoes. He turned prayer wheels with an idle hand as he passed, helped a teenager right a stack of tilting steamers, whispered a move to a pai sho player while the other wailed at him in mock dismay. Sokka tried to keep pace. But the relative lightness of the planet and his cybernetic knee were no match for the endless stairs looping their way up the temple.

“You don’t go easy on the stairs here, huh?” Sokka huffed.

Half a flight up, Zuko deigned to offer him a half-turn. A smile played at his mouth. “We’re all used to it. Most of us get around with gliders, or the flying beasts. But there’s a goods lift we could crack out for you?”

Sokka was a decorated general, a veteran of thirty spans in the arena of war. “I’ll give it a pass.”

Zuko led him to a room on the highest floor and stepped aside to let him enter first. It was airy, panelled with dark wood. A low seating platform dominated the centre, which Zuko ushered him towards. Sokka, sweating a little, took off his parka and eased himself onto a cushion.

When Zuko lit the fire under the teapot, Sokka jumped. The spark that burst from his open palm flared bright, then allowed itself to be stuffed into the brazier.

“Sorry about that,” said Zuko. He was watching Sokka. “Just reheating. I didn’t even think…”

“It’s fine,” said Sokka. He thought, unerringly, of the necropolis around the planet. An orbit of charred limbs. “Don’t worry. Just—” Just what? Habit? Trauma? Sorry man, I just haven’t seen firebending used outside of mass murder before?

“Um.” Zuko pushed a plate of small cakes towards him. The tips of his fingers were stained with henna, red. “Snack?”

Sokka watched him while he nibbled on the cake—mung bean, soft between his teeth, a muted sweetness. “How’s Aang?” he was saying. “Katara? The kids?”

He was smiling. That was one thing the Phoenix King’s portraits never did, but Zuko had lines pressed around his mouth from it. Threads of grey wove into his topknot and his neat, trimmed beard. When Sokka met his gaze, his eyes wanted to dart away by instinct.

“Doing well,” said Sokka. “Aang’s busy, as usual. Katara’s… a menace, bad news for the Fire Nation. Kids are… well, they’re not really kids anymore. I don’t know how much you know.”

“I’ve always wanted to meet you,” said Zuko.

Sokka said, “The privilege is mine to meet such an… honoured friend of the Avatar.”

“I’ve heard about your exploits, of course.” Zuko took a cake of his own. “Teo’s a whiz with the radio. I was getting blow by blow accounts of your victories at the Southern border.”

Sokka chuckled, took another bite. “I do regret we’d not made our acquaintance earlier.”

“You must understand, the secrecy was crucial.”

“If I am to understand, this restoration was your work.”

The seneschal ducked his head. “I could not have done anything without my community.”

It was hard to get a gauge on him. Zuko busied himself with the teapot as it started to steam. Where did his loyalties lie? A firebender with the Phoenix King’s face, who smiled and rode a dragon. Sokka tapped his fingers against the tabletop when Zuko filled his shallow cup with a pale, opaque liquid.

“Butter tea,” said Zuko. “Just like the airbenders used to drink. We harvest the bison milk.” Sokka took a sip. “What do you think?”

It was nice. Creamy, a little savoury: not a flavour profile Sokka had ever expected from tea. “It’s… different from what we drink at home. We make it out of rhododendron. No milk.”

“We cultivate the tea at the foothills,” said Zuko, taking a sip, “and process it ourselves. This one is fermented, with quite an earthy flavour.”

“A tea connoisseur?”

“I couldn’t possibly claim to be.”

Sokka took another sip. “There’s this dinky teashop in the planet system of Ba Sing Se. The guy who runs it…” He looked up. “But I don’t suppose you’ve ever been.”

“No. I don’t suppose so.” Zuko sipped his tea, refilled Sokka’s cup, and set the teapot down with a clunk. “I assume,” he said, and his voice now was all business, “if the Avatar sent you, this is not a social call.”

The cup hovered at Sokka’s lips. Then he put it down, directly in front of himself.

“This is my people. The Southern Water Tribe.” He took the teapot and put it to his right—south, by the compass. “And this is your—the Phoenix King. For the past decade or so, the White Tiger of the West has been impenetrable from attack from the Vermilion Bird of the South.”

“The ice barrier,” said Zuko.

“My brainchild, my sister’s execution. Daggers of ice arrayed to block the ships’ navigation. It’s repelled every Fire Nation ship that’s tried to get through. The arena of war has largely focused on the Azure Dragon of the East.” Directly opposite his own teacup, Sokka pushed the plate of cakes in place. “The Earth Kingdom, with its myriad settlements.”

“And colonies,” said Zuko.

“This means the only route left for the Fire Nation into the White Tiger is through the Azure Dragon, and the Black Tortoise of the North, empty of its Air Nomads”—Sokka traced with a finger, drawing the arc up around his rudimentary map—“before they hit the Northern Water Tribe.

“The North’s defences are… inadequate.” Sokka felt his lip curl, but this was hardly the time to hash out the long disagreement between himself and Chief Hahn. “You’ll know they haven’t been active in the war—I guess they’ve had little reason to be since the invasion we thwarted, oh, decades ago. But once they fall,” he waggled his own teacup, letting the dregs of tea slosh within, “the Fire Nation will be right at our doorstep.

“Without proximity to resources,” said Zuko, tracing the loop of tea paraphernalia, “an impossible route. Almost a full revolution of the galaxy.”

“Not anymore.” Sokka tapped the cakes. “There are enough colonies in the Azure Dragon now to supply the Phoenix King’s forces across the long trek through the north.” He swept his fingers over the empty expanse of table that lay between the cakes and his own teacup. “That’s where you come in.”

A stricken look was dawning upon Zuko’s features. “Me?”

Sokka snagged Zuko’s cup, its tea abandoned halfway. He put it in that emptiness. “And this is you. Emptiness II. The sole inhabited planet in the Black Tortoise of the North.”

“You want me to join the war,” said Zuko.

He sat up straight. Gone was the easy smile, and the solemnity that replaced it did make him look more like his father’s portraits. “Yes,” said Sokka, simply.

Zuko’s henna-dipped fingers drifted over the array on the table. “I have fifty thousand on this planet,” he said. “Refugees, defectors, people with nowhere else to go. People who escaped the war.”

“Yes.”

“You want me to lead them into war, and against my father.”

“To staunch the escalation of war. To cut off their route to the West, and the devastation he might wreak there.”

“We have shrouded ourselves from war, with no intention of joining.”

“The youths I saw in the courtyard,” said Sokka, taking an idle sip from his teacup. The last drops had gone cold in the shallow cup. “What are they training for?”

“Fitness,” said Zuko. “Mental discipline.”

Zuko held his gaze; the proud line of his features was, Sokka thought, unmistakably aristocratic. Then he retrieved his teacup and drained it. When he set it down again, his face was serene again. “You understand I will have to think on this,” he said. “In the meantime, let me show you your rooms. Get you settled and feeling at home.”

Chapter 2: The Amputation of Memory

Chapter Text

He is skimming the clouds. The sea below teeters between blue and green, and it meets the shoreline in clods of foam. How beautiful it looks like this, the shallows still definable from the depths. They flew out from the temple first thing in the morning because he said there was something he needed to show Sokka, and he’d strapped them together, Sokka’s back pressed against his front, and taken them out on the glider. Now they pass the other monks freewheeling on bison and gliders alike, then leave them behind to streak out into the great blue beyond.

“I took you out here,” he says, voice rumbling against Sokka’s back as they hang there in the sky, “because I adore you. You are my one treasure. Against the will of the monks, I want to take you as my wife—”

Aw fuck. Not again?

And then Sokka is freefalling, careening into the sea—

He woke up on a big hard bed with Emptiness bright and white, high in the sky.

He floundered out of his blankets. The room they had put him in shared the top floor with Zuko’s and the view outside was beautiful, blinding sunlight highlighting the contour of each mountain. From this vantage point he could even see the distant blue expanse of the swollen sea.

His stomach growled. Sokka pulled on a fresh set of clothes and made his way back down the infinite stairs.

The temple became busier as he descended. He nodded to the pointing onlookers, bustling about at their daily tasks, as they spotted him. Towards the bottom, a man in a hoverchair accosted him.

“I see you’re finally up,” he said jovially. A crop of wild hair sat atop his brow, with some attempt to tame it into a knot. Lines were carved deep around his mouth and at the corners of his eyes. A toddler squirmed in his lap.

“Yeah,” said Sokka, blinking. “This planet rotates faster than mine, I didn’t realise… Sorry. I’m Sokka.” He bowed.

The man cocked his head. “No problem. The big guy”—he must mean Zuko—“asked me to look out for you. I suppose you’re hungry.”

He turned the chair and started down the stairs. Sokka, with nothing better to do, followed. “I’m Teo, by the way. This is my youngest.” He told Sokka the name of the toddler, which he promptly forgot. “We’ve heard all about you, of course. You’re a legend. My dad is especially—”

“Wait,” said Sokka, wincing in the glare when they passed a window and wishing he had brought his snow goggles down, “what time is it?”

“Hour of the snake,” said Teo with a laugh. “Don’t worry. You’ll get used to it soon.”

Sokka, with his wealth of experience travelling, knew that. But the smell of food, mmmm! came wafting through and then they were in the kitchens, big and steaming and heaving with life. “Morning, chefs!” crowed Teo. The toddler made a valiant attempt to wriggle out of his lap. “Famed and famished general coming through.”

Sokka found himself fussed over, cheeks pinched and told that he was too thin. He left with a tray laden with congee and little dishes filled with curry, another cup of butter tea, and a white lump he thought might be cheese. Teo led him through the labyrinthine stairways and hallways of the temple, chattering all the time.

“Laundry’s down that corridor. Ask them for extra blankets if you need. The resident doctor’s over here, if you ever need the heat in your chi redirected. But check when she’s in, cos she might be out making paper.” The toddler reached a sticky hand towards Sokka’s tray; Sokka sacrificed his cheese. “There’s another one out in the outlying villages, specialises in earth medicine. Oi! Very important general coming through!”

They burst into the courtyard. Monkey-pigeons and people alike scattered. A few people called morning! to Teo, who made the toddler say morning! back. They rounded the building, passing a room where black smoke huffed from a chimney. “The smithy,” said Teo, and poked his head inside. “Morning, Toh-ki!”

A hulking figure, silhouetted before the furnace, raised a hand in brief greeting. “She’s a good one, always executes my dad’s fantasies. Made this baby for me”—he patted the side of his hoverchair—“based on Dad’s design and it still works like a gem, even decades later. Doesn’t talk much though. Aaaaand here’s the man himself!”

He flung the next door open. Inside, the room was crammed absolutely full: blueprints plastered upon the wall, shelves full of parts and models and little drawers, half-built contraptions on the tabletops and on any spare patch of floor. It took Teo beelining inside, the chair nimbly floating over the miscellany on the floor, and the toddler chirruping, “Ah kong!” for Sokka to notice the tuft of white hair bobbing among the piled machines.

“Hello, sir,” said Sokka as he picked his way through. Something clattered to the floor.

“Leave that,” said the old man inside. He hobbled out from behind the piles, zanier than even his son in appearance and half the size of Sokka. “Oh General, it is an honour. It is a real honour.” The hand not gripping his walking stick came out to claw at Sokka’s: cool, sun-spotted, with little mechanical joints attached to the arthritic knuckles. “They call me the Mechanist.”

“You see a machine around here, it’s his,” said Teo proudly. “Designed the lifts, the gliders, the delivery belts in the village… He made me this chair. I’ve even got a pair of boots, if I wanna get up and walk around.” He pointed to a chunky pair sitting on the windowsill.

“I’ve been working on a grain harvester. Could make the harvest faster. Figured out how it can work on slopes but the main issue is making sure it doesn’t crush the plants to paste. Anyway”—the Mechanist nodded now towards Sokka—“we’ve heard all about you, of course. The ambush at Fish III, what a spectacle that was!”

“How do you get your news here?” said Sokka. For a population that no one knew of, the settlers were curiously abreast of the galactic news. “I don’t suppose Aang comes down with the book of annals.”

“Oh, no,” said the Mechanist, easing himself onto a stool. “The Avatar doesn’t visit often. He is quite busy.”

“I’m on the radio,” said Teo. “I can tune into pretty much any frequency I want.”

Sokka, who had long-range radio on his ship for journeys like these, said, “Even the clandestine channels? All the way out here?”

“It was a matter of restoring the Air Nomads’ old signal towers. Took a while but it was worth it. If I know about a channel, I’ll find a way.” He tapped his temple with a wink.

“How did you two come to live on this planet?”

The Mechanist sighed. “Oh General, it’s not a story I’m proud of…”

“Ah-pah, you were in desperate circumstances. You can’t be that hard on yourself for things that were outside your control.”

The Mechanist shook his head. “The Avatar wasn’t happy when he found us. But he is compassionate. And he encouraged us and our small band to join the seneschal here, when the planet came under his stewardship.”

Teo patted his father on the back. The Mechanist scratched the toddler’s head. What a picture they painted, Sokka thought, the three generations in one tableau. “It’s been a journey for all of us. But I’ve raised all my children here—”

“—I would’ve done the same,” added the Mechanist, “if I could.”

“Sokka.”

They turned. It was Zuko, peering in through the door with a bright, expectant look. He nodded at the Mechanist and Teo and the toddler, then returned the beam of his attention to Sokka. “You slept well… I trust?”

“Very soundly.”

“I’d love to show you around,” said Zuko in a rush. “We so rarely entertain guests. If I’m not impinging…”

“No, of course not!” said Teo, with a meaningful look that Sokka didn’t know how to interpret. He moved the hoverchair out of Sokka’s way and swept his arm wide over the cleared path. “General.”

Sokka, who had been starting to quite like Teo, considered revising his opinion. He followed the seneschal out and into the daylight.

“They are lovely,” said Zuko. “I hope they’ve made you feel very welcome.”

“They’re interesting,” said Sokka, and he meant it.

“I thought I should give you a proper tour of the settlement, now that you’re freshly awake.”

“Lead the way.” Sokka was imagining, rather distantly, the sky bison ride he had taken with Osha yesterday. Then they hit the courtyard.

Sokka baulked. “I’m not getting on that.”

“That,” said Zuko, “is my baby.”

Zuko’s baby, a fifty foot dragon, huffed. Great white plumes of smoke issued out of his nostrils and buffeted around Sokka. “Play nice, Druk,” said Zuko, laughing.

“I don’t care if that’s your baby or your cousin or your aunt, I am not getting on it.”

“Him.”

“He is going to kill me!”

Zuko approached the dragon. His great fire-breathing snout nudged into Zuko’s hand. “What,” said Zuko, “is the great victor of Fish III not game?”

“He’s not,” said Sokka flatly.

Which was how the great victor of Fish III climbed upon the back of the great serpent Druk.

Zuko sat in front of him, smoothing a hand down the dragon’s neck. Unobserved, Sokka let his lip curl as he watched Zuko from behind. He seemed less skittish now he was reunited with the dragon—what was he plotting?

“Hold on,” said Zuko.

“To what?” Sokka might’ve said, if the dragon did not choose that moment to take off. Sokka clung onto Zuko for dear life. The bastard whooped.

Druk shot like a firework into the sky. They rose past the trees, past the jeering paper faces of the children’s kites, past the gliders, past the roof of the temple. Zuko was laughing, chest heaving in exhilaration under Sokka’s hands. And when Sokka chanced a look down, the sight of the vertical drop into the valley below made him screech and mash his face into Zuko’s back.

“You’re missing out on the view,” Zuko shouted over the wind.

He was evil. He was evil and he was out to murder Sokka. “You’re going to leave marks in my skin,” he said, which Sokka felt as vibration more than heard.

“I’m not letting go!”

But curiosity did get the better of him; that was one of his strengths, really, his infinitely curious mind, so open to knowledge and learning. That was the basis of his ingenuity. So he cracked an eye open.

The patchwork of vistas slid below them, the cold scraped itself across Sokka’s cheek. Druk wended through ice-capped peaks and the sheer rock faces whipped past. And noticing that Sokka had emerged to look, Zuko started up his commentary. He raised his voice over the wind to regale Sokka about the communities that lived clinging on wooden supports to the vertical mountainside, how they had reconstructed the design from surviving frescos in the temples. A cluster of horned beasts perched beside the huts, watching them fly across. They gusted past forests of oak and pine thick with foliage, as though the fires of hell had never torn through. It had been a deceptively difficult task to regenerate this; the settlers had arrived on the planet to find it overrun monocultures of whatever had survived Sozin’s inferno, and this was the product of the settlement reviving the balance of the ecosystem.

A flock of birds kept pace with them as Zuko urged Druk down to the agricultural plains. The plateau stretched into the horizon, golden with wheat and millet and barley entering the harvest season, patchworked with fields of vegetable and fruit and soybean. “With all the earthbenders at our disposal,” he said, “we can grow more varieties of crop and more quickly regenerate the soil, meaning the footprint of our land use is much reduced…” And then he took them to the foothills that sloped in the direction of the rat, towards the sun, ringed with camellia bursting with white blossoms. This was where they produced their tea—not the variety Sokka tried yesterday, no, that one was grown further east, at a higher altitude—this one had a more delicate flavour and colour and he wouldn’t put butter in it, he could brew it for Sokka when they got back. They streaked down close enough to wave at the labourers processing the leaf in the villa, then twirled back up into the sky.

And Sokka looked upon the bountifulness of the planet and started to tabulate. How much did they produce? What could be stored—dried, salted, fermented? What was their surplus? How much could be taken on campaign and how much could sustain their troops? If the planet were besieged, life would probably go on as usual—it was incredibly self-sufficient.

It was a helpful exercise. He quickly forgot the drop below.

In fact, he became so lost in his thoughts that it came as a surprise to him when they began to descend. They had come to a verdant patch, tucked like a bookmark between the jagged rock faces. Druk circled lower and lower, then landed in the valley with a thwump in the lush grass. The sudden beauty jolted Sokka out of his calculations, and Zuko had to tug him down by the elbow.

“You can see more if you come down.”

“Is this—” Sokka let the grass sheaf through his fingers. He shook his head. “Is this real?”

“One of the most beautiful places in the galaxy, I think,” said Zuko, hushed. The green, so lurid it felt unreal, a shade Sokka was certain he had never seen before, was dotted with wildflowers that swayed in the breeze; it crawled up the surrounding mountainsides until it gave way to ice and stone. Dozens of rivulets drew shining tear tracks down the rock. “The beyul, a sanctuary to the Air Nomads. The veil between our world and the world of the spirits is thin here.”

For all his agnosticism Sokka could appreciate why the Air Nomads might have thought that. He stumbled in Zuko’s wake along a modest path that cut through the grass, past a couple of feeding sky bison and twittering black and white birds, leading to a wooden house that crouched low so it would not interrupt the view.

“Beautiful, aren’t they?” said Zuko, pointing to the birds. “They cropped up in the last year or so. I don’t think they’re native. I asked Aang and he didn’t know anything, but they’ve blended in quite naturally with the ecosystem. I couldn’t bring myself to cull them. Refugees, like us.” Then he touched the door with his knuckles. “Anyone home?”

“Come in, seneschal,” called a woman’s voice from inside.

Zuko nudged the door open, gesturing for Sokka to step inside. The house was dim, herbal-smelling, warmed by a brazier burning low on the ground. Wooden drawers lined the walls, and anatomical charts were wheatpasted to the wall. The occupant knelt upon the ground, wrapping a packet of paper. She was thin, hair drawn back into a chignon that showed the skin clinging to her cheekbones. “You’re the general, aren’t you?”

“One and the same,” said Sokka. “And you are…?”

“This is Doctor Song,” said Zuko, coming up behind to kneel upon the floor. Sokka copied him. “A talented physician from the Earth Kingdom.”

“My late mother and I hailed from Chaff IV in the Winnowing Basket mansion. We joined the seneschal after suffering regular harassment from passing Fire Nation troops,” said Doctor Song. “No maladies, I trust, General?”

“I think not, besides the encroachment of age.”

That usually drew a chuckle. The physician merely nodded. “If you would lend me a little time, I could perform a quick, routine check-up.”

“Oh, that’s not necessary.”

“Doctor Song is very skilled,” said Zuko.

“Oh, of course.” Sokka favoured her with an affable nod. “But my sister’s a healer too, she would’ve fixed me if anything was wrong.”

“Just your pulse,” said Song. “No longer than it would take for an incense stick to start shedding ash.”

Sokka looked to Zuko. The seneschal nodded in encouragement. So keen; what ploy was this? He pulled up his sleeve.

The physician wiped her hands on a damp towel, then pressed three cool fingers to his wrist. She was quiet for a while, head tilting.

“What’s the verdict?” said Sokka. “I'm still alive?”

“Your leg. It pulses differently from the rest of your…” The fingers pressed harder. “Ah. A replacement?”

“Yes,” said Sokka in surprise. Doctor Song tapped his left knee—the correct one—and Sokka drew up his trouser leg. The wiring glowed in the gloom. “The knee and some of the leg below.”

“All mechanical.” Her fingers ghosted over the exposed metal.

Zuko’s mouth had fallen open. “What happened?”

“Fell out of aircraft when I was a teen. Fighting Fire Nation, you know how it is.” He winked. “The planet’s attraction was pretty strong. Never felt the same again—not until this baby.” Sokka narrowed his eyes at Song as her fingers found his pulse again. “How did you…?”

Her eyes had fallen shut. “Hmmm. Extra energy charge around the mind.” She raised her head to glance at his temples; Sokka knew she was looking where the blue arrows glowed. “But of course. A true Southern Water Tribesman.”

“My namesakes,” said Sokka. He tapped his temple, wry. “All squeezed into a chip the size of a fingernail, and locked up in here.”

“Indeed.” Song smiled. “General, you are for your age a healthy man. No doubt given the nature of your position you must remain active.”

“Good to hear.”

“I do, however, detect a little stagnation. Unusual, given—again—the nature of your position.”

Sokka raised an eyebrow. “Stagnation.”

“Issues with stress, lethargy, emotional instability…”

Sokka yanked his hand back. Too fast, too fast. His tells were slipping. Zuko was watching. He shook the sleeve over his wrist, smiling widely at the doctor. “Thank you for your time, Doctor Song.”

. ݁₊ ⊹ . ݁ 𓅪 ݁ . ⊹ ₊ ݁.

“There are some people I want you to meet,” said Zuko when they mounted Druk again.

So the dragon looped down from the alpine heights, following the slope as it undulated downwards and then into the abrupt crash of the sea. Sokka swallowed against the pressure building in his ears. Druk, a long shimmering line, followed the cliffs created by the risen sea until he reached a rocky shore. They leapt off. Sokka spotted huts clinging to the cliffside rising above them and before them was the long, blue expanse of the water. Zuko lit a flame in his palm.

“Druk,” he said. And from the dragon’s mouth came a whorl of—it was fire, but unlike any fire Sokka had ever seen. Technicolour, like a sky ablaze during the winter nights. The dragon’s fire hit the flame in Zuko’s palm, which shot upwards in a jet of colour and exploded high over their heads. “They’ll come soon.”

He sat down upon the shore, against Druk, and looked out over the sea. Sokka, after some time, sat too. Looking over this seascape, where sky melted into sea, he could almost imagine himself back at Jade Well IV.

The silence stretched. Ordinarily, Sokka would fill it, but he was sitting with the son of the Phoenix King, a man he had yet to make a measure of.

Zuko cleared his throat first. “The old shoreline was—” He gestured into the horizon, somewhere far out. “Emptiness is a cold sun. When the glaciers melted, the sea levels rose nine feet. So, not many beaches left on this planet. They’d take centuries to form.”

“We have beaches where I’m from,” said Sokka. “Sand all black, sparkling like a winter night.”

“I miss swimming at the beach,” Zuko sighed. “Building sand sculptures. I used to do that with my sister. I hear she’s a sage now.”

Sokka’s ears pricked. The subject of the Phoenix King’s heirs was a closely guarded secret and this was the best confirmation he’d get as to their number, gender, and perhaps age. “You have a sister?”

“We’re alike in that way,” said Zuko. “Both older brothers to a sister.”

Sokka filed that away. One female heir, younger than Zuko, likely by just a handful of spans. Surely Aang had known all along, and had simply not divulged because of his source. “What a coincidence.”

“Hmm? Excuse me.” Zuko made an apologetic face. “I’ll sit on your other side,” and proceeded to do exactly that while Sokka followed his movement with guarded bewilderment. “I don’t hear as well in the left ear,” he explained. “I try to keep people on the right.”

“Really?” Sokka craned around to look at the burn scar before registering it might be rude, but Zuko turned to give him a better view. “And your vision too? If you don’t mind me asking.”

“It’s not as clear as the right.”

“You never thought of cybernetics? Could rewire those nerves for you in a jiffy.”

Zuko’s mouth pinched. Before he could reply, a jet danced out of the ocean, snaking through the air before splashing back down before them. Zuko shot to his feet. “It’s them.”

They were two figures growing larger and larger amid the endless blue, heralded by a huge white spray of water. Druk huffed in excitement, sending up more rainbow sparks. As they neared, Sokka could see they were… surfing over on a huge ice floe powered by nothing he could see.

As in, it was powered by waterbending.

Sokka stood up. The floe veered up to the shoreline with the biggest spray yet, and then the pair ran giggling to embrace Druk’s waiting snout. Zuko let them play out their greetings, then cleared his throat.

The waterbenders turned.

They were twins, a pair of moon-faced girls around Kya’s age, dressed in the garb of Emptiness II dyed blue. They looked shyly at Sokka and bowed to greet him—a greeting that was decidedly not Water Tribe.

“Sokka, I’d like you to meet the girls. Siqiniq”—the one with twin braids nodded—“and Taqqiq.” The other, with a pair of hair loopies like Katara’s, ducked her head in acknowledgement.

Siqiniq and Taqqiq, the sun and the moon. Such familiar names in such a distant land. “You’re Southerners too?” said Sokka.

The youngsters exchanged a glance. “Our parents were born in Jade Well IV,” said Taqqiq.

Sokka’s breath caught. One by one, he pulled them close, pressed his nose to their cheeks like they were family. Perhaps they were. Perhaps there was a Sokka in his head who was the forefather of these girls.

“You waterbend?” he said. “What can you do?”

Taqqiq pulled a glob of water from the sea. It rotated above her, large as a tiger-seal, the sun sparkling through it and dappling her with its light. Siqiniq reached out with both hands and yanked; before Sokka knew it, the twins had pulled the glob into an ice sculpture in the shape of Druk. His jaw dropped. They had made it look effortless.

“I’m especially proud of them,” said Zuko. “They’ve been travelling down to the pole to rebuild the ice there. This is our endeavour. The Air Nomads believed rebirth followed death. Emptiness II brought back from death, imbued with the life of its former inhabitants.” He rested a hand on Siqiniq’s shoulder. “And these two developed the techniques between themselves, with Katara’s input whenever she was able to visit.”

“Between yourselves?” said Sokka. “But what about… Don’t you have… Were the memories destroyed too?”

The girls exchanged a glance. “We were both born… here,” said Siqiniq haltingly. “We’ve never had any contact with the Water Tribes.”

“You don’t have it,” said Sokka, realising. And the horrible confirmation when he pulled back: there was no telltale gleam of neon at their temples, pulsing with the memory of every namesake that had ever walked the galaxy before them. “But Siqiniq, that’s the name of my mother’s mother. And Taqqiq, you share a name—you are—”

He shook himself. No, the girls would always be themselves, of course they would—only without that eternal well of collective memory to drink from.

And Sokka’s chest ached at the injustice. To be a Southern Water Tribesperson without even a fragment of memory of your namesake, of atiq—was that even possible? Not only a limb amputated, but a soul; bereft of the burden of their lifetimes.

. ݁₊ ⊹ . ݁ 𓅪 ݁ . ⊹ ₊ ݁.

On the journey back, Sokka barely registered the frigid alpine wind buffeting against his cheeks.

“Sokka… Sokka? Hold tight.” Belatedly, Sokka felt a hand over his, adjusting his grip around Zuko’s waist. Then, a prod: “You alright?”

“It’s nothing.”

They flew in silence for a while. “Katara… she mentioned to me her chip was… incomplete? And the necklace she wears is a locket—”

“The Katara who held it before her,” said Sokka, “was burned to a husk by firebenders. Then they dug into her brain, plucked out the chip, and ground it under their heels. And now my sister carries the irreparable shards of her past lives they could not piece back around her neck. Like a noose.”

“I see,” said Zuko. And lapsed into silence.

. ݁₊ ⊹ . ݁ 𓅪 ݁ . ⊹ ₊ ݁.

Sokka’s rooms, when he returned to them, were a sanctuary. He threw himself into the waiting bath and didn’t think too hard about how the water had been heated. When he climbed out to dress, a slip of paper, folded up as tiny as could be, fell out of his clothes.

He eased it open with pruney fingers. In cramped writing, it said, Dear Uncle,

Sorry we didn’t get to chat more while you were back. Anaana was keeping me away. It’s what I’m writing about, actually. When we were kids she fed us on all her and ataata’s and your war stories. You guys were just kids too. But I’m grown up, even Bumi’s been recruited for years, and I’m not allowed to do anything. I’ve been exemplary in all my tactical waterbending, which she taught me! But she pushes me towards healing and won’t let me go on any missions my classmates are now all taking up.

I’m not dumb. I know why. My dad’s the Avatar, but I wish I didn’t have to live my life as HER avatar of everyone who came before me…

The handwriting, if it were possible, became even smaller, more cramped. I wish I could’ve come with you. They told me it was top secret, even though I argued that she obviously trusted you and you’d always keep me safe. I miss you. Feels like you’re taking longer and longer missions, these days.

Good luck, Uncle. See you in one piece soon, I hope.

Kya

. ݁₊ ⊹ . ݁ 𓅪 ݁ . ⊹ ₊ ݁.

With his late rise and the quick rotation of the planet, Sokka found himself restless when the settlement turned down to sleep, his niece’s letter turning in his mind. It was dark under the shattered remains of the moon, which itself was only visible as a jagged sliver halfway up the star-encrusted arc of night. He idly wrote out a message to Aang, then took a lamp down to the Mechanist’s workshop.

The machines hummed sleepily when Sokka stepped in; the lamplight threw their hulking shadows against the walls. Teo’s radio room was adjoining and the radio took up most of it. It was a complex contraption. But Sokka had a knack for engines, and even if he didn’t there was a Sokka in his head who had been a keen radiographer. He got it whirring.

He dialled into Aang’s private channel, tapped the microphone. Then, he murmured, “It’s a strange place. He showed me the plantations, the sea. I hope you’re happy to see your planet repopulated. Zuko’s not given me an answer yet. He’s… surprising. Give my love to Katara and the kids. Tell Kya I’m thinking of her. Standing by for further instructions.”

There it went, beaming out across the galaxy. In a couple of days, he estimated, it would reach Aang all the way in the southern end of the White Tiger. Then his feet took him back upstairs.

It took him a while to realise this wasn’t his room; he had followed a gleam upon the wooden floors, and it had taken him to a vestibule where two candles and pricks of incense light burned. They illuminated a small altar, upon which sat a small bodhisattva behind piles of cakes and fruit.

Sokka knelt. It was a bronze statue, which might’ve explained its survival after Sozin’s inferno. Maybe Aang had been taught to kneel like this, a century ago, a lifetime ago. He wasn’t sure what else to do. The planet was reborn; were the souls of the airbenders reborn into it? He thought of Kya’s letter and wondered how much of his mother lived now in his niece.

“Hey,” he said, a conspiratorial whisper. “What do you guys think of him, really? You reckon he’s genuine about all this restoration stuff?”

And answering him came a low human-sounding hum.

Sokka froze. There, unmistakably, kneeling beside him, was an old monk: robes a crash of colour in the gloom, a tattoo snaking out of his collar over his bald skull. A tattoo only one living person in the galaxy had. When the monk turned, Sokka saw his eyes black as ash.

Sokka leapt backwards. When he looked again, the monk was gone.

Chapter 3: Relics

Chapter Text

“Oh yes,” said Zuko, “the temple is haunted. We should’ve warned you, but we’re all used to it by now. It slips my mind.”

Sokka had found him in the main shrine of the temple, offering morning incense. Before him towered great polished bronze statues of airbenders past (scuffed, still, in areas that the elbow grease couldn’t fix), serene on their seats of lotus. At their feet were garlands of flowers, and hundreds of porcelain urns. When Zuko concluded his morning prayers, he propped a basket of cabbages on his hip and strode past Sokka with a briskness that spoke to his familiarity with the hallways.

Sokka, at a loss for other activities he could be occupied with, followed. “Oh yeah, I’m forgetting about the lost souls haunting my own house all the time.”

Zuko shrugged, casting a wry look back at him. “It was their house originally.”

He was holding back, Sokka was certain. All he needed was a chip in the armour, let his guard slip. “Listen, I’m sorry for what happened yest—”

“No, no,” said Zuko, “the fault was mine. It’s a sensitive topic, I shouldn’t have asked.” And then he turned into the dining hall.

Breakfast had been cleared, but the long tables were heaped with dough and piles of chopped vegetables. A veritable production line was going: kneading dough, chopping and rolling it out into flat discs, then filling and folding them into little pouches. “Seneschal!” cried one cook. “There you are.”

“Morning, Ling-jie,” said Zuko, dipping down with far too much grace to submit his cheek to a floury pinch. “Your cabbages, as requested.”

“Good! Nur, go wash and chop these.”

A young woman shot up from the bench with military responsiveness, then carted the cabbages to the kitchens. Zuko settled into her seat, folded his sleeves up, and started to dutifully wrap. When Sokka looked up, Ling’s critical gaze was fixed upon him.

“Well, General. Can you wrap?”

The dumplings didn’t look dissimilar to the steamed buns or dumplings you might find on the outskirts of Ba Sing Se, that sprawling multi-planet settlement in the Tail mansion. “I’ve never…”

“Oh come on, it’s easy. And quite fun,” said Zuko, and he produced a neat little pouch in his palm. “We’ll show you.”

Sokka found himself crushed between Zuko and Ling, sweating as they drilled him in the art of momo folding—on Emptiness II, no mouth would be fed if its owner’s hands did not put in the work. Sokka’s came out lopsided, the pleats uneven, desperately underfilled because Zuko had suggested that perhaps Sokka be less ambitious in his first attempts. But there was a rhythm to it: collecting the disc of dough from the centre of the table, dolloping the chopped vegetable filling inside, pinching and turning the package to seal it.

“Are these all vegetarian?” said Sokka.

“This batch, yes,” Ling grunted.

“We prefer to follow most of the customs of the departed Air Nomads,” said Zuko as Sokka wrinkled his nose. “We do not keep livestock for meat; the bison provides us with its milk and fur.”

“We can actually grow some meat,” the kid Nur piped up, relocated somewhere further down the table. “The same method they used to revive the fauna in the early days.”

“Siqiniq and Taqqiq’s family are good hunters too,” said a young man further down who’d introduced himself as Ujarak—it was a name Sokka recognised from some other southern settlement of the White Tiger, the Net mansion perhaps. “They only harvest what they need.”

“It just wouldn’t do to introduce flocks of foreign species deliberately,” said Zuko. “It’s so mountainous here we’d have a hard time letting them graze, or their feet would trample all the restored earth…”

“And I,” said Ling, “make some pretty mean mock meat.”

“Well there’s no need to mock your meat,” said Sokka with a wink. “I’m sure it’s perfectly nice.”

“Seneschal?” someone called from the doorway. They looked up. “Got an order of fertiliser we need transported…”

“Got it,” said Zuko, rising from the bench. He wiped his hands on a cloth and clapped Sokka on the shoulder as he climbed out. “I’ll leave you in their capable hands.”

“Wait—” said Sokka, thinking about ledgers and troops and rations again, but Zuko was already sweeping out of the dining hall.

. ݁₊ ⊹ . ݁ 𓅪 ݁ . ⊹ ₊ ݁.

When Teo came zooming by in his hoverchair, Sokka had managed to fold a painstaking twenty momos—but the cooks had whisked them off to steam right before Teo’s arrival, so Sokka had nothing to show for his efforts.

“There’s flour on your nose,” said Teo with glee. He had a child in tow again, and upon closer inspection it appeared to be a different one: ambulatory, certainly older, and capable of enough speech to greet Sokka with a polite, “Good day to you, General.”

“You need to get me out of here,” said Sokka.

“You’re in luck. I figured if you’ll be here for a while, you need a way to get around.”

Sokka thought about Zuko charging off on Druk, punching through the mountaintops to goodness-knows-where. He needed a way to catch up.

Unfortunately, what Teo had in mind was a gliding lesson with his child.

Sokka regarded the glider that Teo had fished from one of the temple’s storage rooms with reservation. Aang had a glider, a simple affair: a staff that snapped open two sets of wings at the push of a hidden lever. This was nothing like that. It came in a rucksack that tied around the waist, and by pulling a string would unfurl into a frame of canvas and wire, pulleys and levers. It looked incredibly flimsy.

“What?” said Teo.

“I was thinking, you know, a sky bison…”

“They aren’t cheap! And you’ve gotta feed them. Have you seen their turds? Massive.”

“I just—” said Sokka. He sighed. “Can I be taught by someone who’s more than six years old?”

“I’m TEN,” said Teo’s spawn.

Teo barked out a laugh, giving him a nudge with the chair so he stumbled. “Come on, we get the kids gliding from when they turn three. She’s an old hat. Better than me! I don’t even have the legs to show you how. You game?”

Sokka had faced infernos supercharged by the stars, had brought down entire legions with his wits alone. His name alone shook fear into his enemies. He was not game.

. ݁₊ ⊹ . ݁ 𓅪 ݁ . ⊹ ₊ ݁.

When Zuko found him again, he was dangling from his glider by one arm over the face of a cliff and Teo was flying loops around him in a glider attached to his chair, laughing uproariously. The child, clearly raised wrong, had long fucked off with her friends after they had made special effort to veer by to jeer at Sokka’s efforts.

“Don’t take it too personally,” said Zuko. “They all start flying as children, so they are easily amused by adults with no flight experience.”

“I have flight experience,” Sokka groused. “I’ve piloted atmospheric and interplanetary craft since I was twelve!”

Teo and the child had the good sense to tether Sokka to the ground, though a soft landing was not guaranteed. Now, Druk nudged his long neck under Sokka. Only yesterday, Sokka could not have conceived of finding a sense of safety upon a dragon’s back. Zuko reached over to pull one of the levers and the glider twisted shut.

“There we go. Not so hard, was it?”

They were on the ground again: beautiful, familiar ground. Sokka had never been more grateful for it, though he would never make the mistake of taking it for granted again. Before Zuko, however, he smoothed his expression swiftly. “Ahem. Well, I do thank you for your timely—ah—intervention, seneschal.” Then, “I was meaning to ask—”

“Can it wait?” said Zuko. “They need me to record the latest harvest and distribute the batches…”

Sokka, his mind latching back onto supply, said, “I can help.”

“Nah,” said Zuko, already turning to mount his dragon again. “You’re our guest. I’ve got volunteers already. If you find Osha she can…”

Sokka watched him fly off, the wind eating his words, then let the irritation seep back into his muscles. He shouldered past the kids drilling martial arts, again—except this time they weren’t kids, they were young adults training with long wobbling bamboo poles. He watched the display for some time, his fan tucked under his armpit: the youths striking, turning, responding with military precision to the rhythm of the drummer. What were they training for, if not for this? Then he stalked away.

“Anyone seen Osha?” he called into the Mechanist’s workshop, which only thrummed in reply; and the smithy next door, where Toh-ki merely shrugged and the apprentices hammered away as though he hadn’t spoken. He wandered back into the temple. “Osha? Osha?”

The next room he stumbled into was occupied by a saffron-robed spectre with a half-melted arm. Sokka decided to end his search for the day.

. ݁₊ ⊹ . ݁ 𓅪 ݁ . ⊹ ₊ ݁.

With the seneschal so otherwise occupied, there wasn’t much for his esteemed guest to do besides make enquiries as to his location—unknown—and then hover around the Mechanist’s workshop and shed his awkwardness around the familiarity of machines.

Sokka liked machines. He had a knack for them. He liked how they were put together, how you could take them apart and see how each part fit into the whole. The Mechanist kept him busy with fixing a pile of gliders that he needed younger, defter fingers for.

When Sokka hauled the repaired gliders off the table for the runner who’d come to collect them, he unearthed a pile of blueprints. The Mechanist’s lines were trembly but sure, etching out a number of designs. Sokka leafed through. Ships with sails that would catch the energy of the sun, helmets for the vacuum of space with forcefield visors, weapons powered by fire…

Wait. Weapons?

Sokka inspected the blueprint more closely. He’d been on the blasty end of enough Fire Nation weapons to recognise how they worked, and the mechanism was eerily similar: the explosive, the projectile, the barrel, and then of course the blasty end itself—

“Looking for someone?”

Sokka jumped as an arm came to slam down upon the blueprints. “Shit. Warn a guy, won’t you?”

Teo parked himself at the end of the table, grinning. “The hoverchair’s not the quietest.” He had a bowl of noodles, swimming in glistening red oil. “Got an eye on our seneschal, have you?”

“I’ve been sent by the Avatar to collaborate with him.”

“Collaborate, alright.”

“I’m sorry, what? I’m his guest and I haven’t seen him for days.”

Teo leaned in. “He’s never taken a lover. Too noble, you know?”

Sokka did not say, Why are you telling me this. “I don’t.”

“He’s refused some very generous dowries.”

“Like yours?” said Sokka, more sardonic than it had sounded in his mind.

“Well, my dad’s, since he would’ve footed the bill.” Teo winked, then slurped his noodles. Sokka’s gut curdled. Oil splattered onto the blueprints. He got up.

“I’m going to find better company.”

“Oooh, touchy!”

Sokka stalked out of the workshop. But luck was on his side today, because he caught the hem of a familiar burgundy robe flicking around the side of the temple.

There he was, finally. Off the beaten path. Sokka’s senses prickled. Where was Zuko off to, all alone, after shaking off Sokka’s tail for days now? He hurried to catch up.

Sokka followed him around the back of the mountain, as an orcabear might tail its prey, along a precarious and at times steep path. There were plenty of rocks to hide behind, and the lack of weeds to stumble over told him this way, though hidden, was well-trodden. So Zuko ventured out here often, Sokka thought, peering as his shape up ahead rounded another curve—and this far away from the settlement clearly had something to hide.

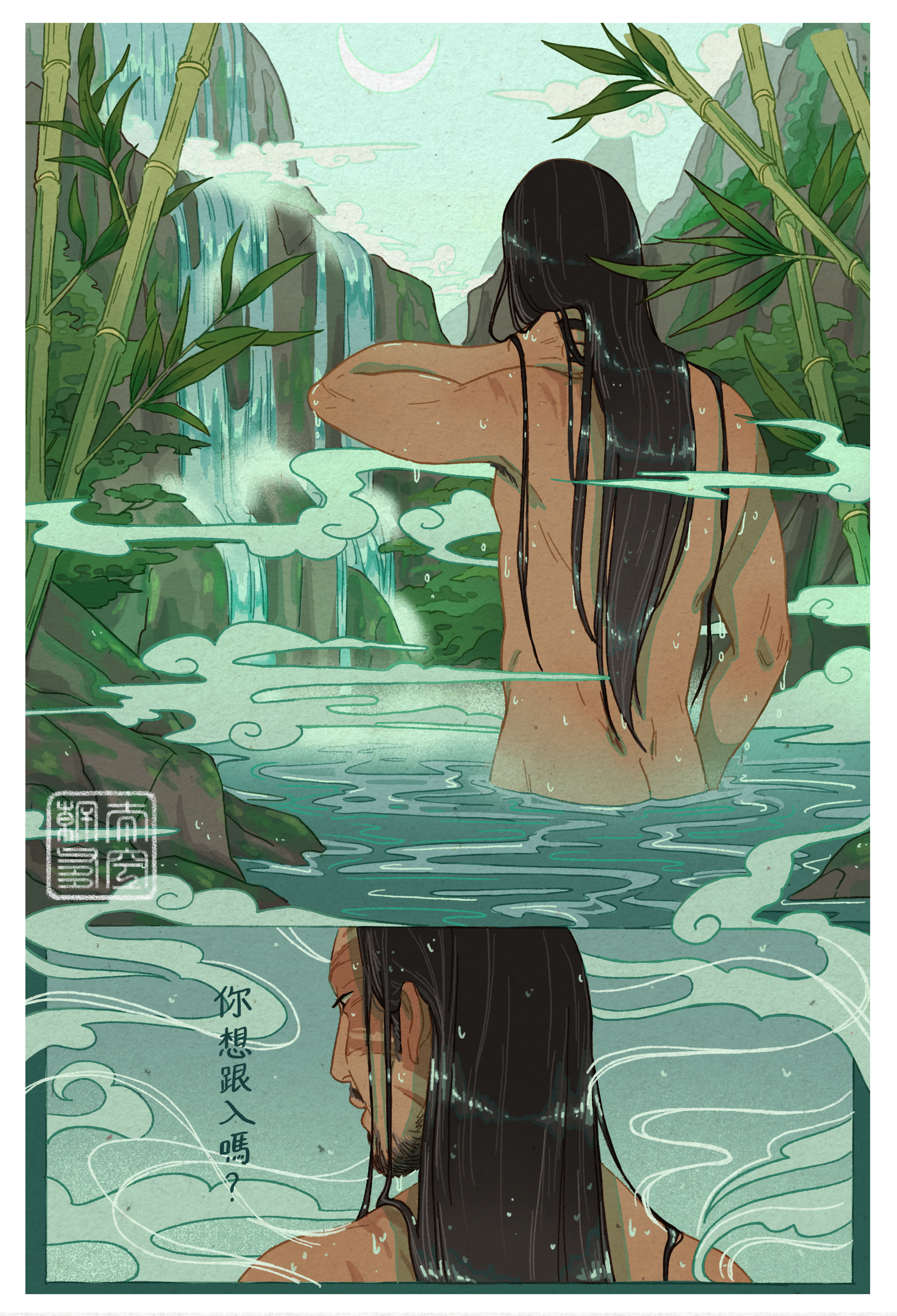

He heard the sound of trickling water, Zuko’s footsteps slowing down and the scrape of him climbing down rock. Sokka stayed put, crouching behind a rock. He peered around to survey the seneschal’s movements—and froze.

Below, Zuko’s robe fell over his broad, bare shoulders. It puddled upon the ground. The delicate slop of water, stepping in; the louder splash as he submerged in neat ripples under the misty water. Sokka’s breath lodged in his throat. And then, after a whole era it seemed, Zuko’s dark head broke through the surface. His hair was a slick sheet down his back. The droplets trailed down the swell of his chest like the rivulets in Doctor Song’s beyul, steaming on his skin.

And then, mortifyingly, Zuko spoke.

“Are you gonna stay there all day, or are you getting in?”

Sokka wrenched his head back around the stone. His pulse skittered against his ribs. There was no way Zuko could have seen him, was there? His back was turned, that long line of grey-threaded black falling sleek and wet behind him. Sokka squeezed his eyes shut, counted to ten, and crept away back down the path.

And was it his imagination, or did a wry chuckle follow as he left?

. ݁₊ ⊹ . ݁ 𓅪 ݁ . ⊹ ₊ ݁.

Osha he finally found after taking a wrong turn to lunch, some two floors above the dining hall. He was following the sound of chatter, not yet smelling a delicious steaming hot meal but hopefully close, and when he burst through the doors he stopped in his tracks.

“Oh!” he said. “Osha.”

She was standing in the middle of an airy hall, long pointer stick in hand, instantly commanding even as she was surrounded by an assortment of Emptiness II’s denizens. Arranged around the room, all about them, were crates—stacks and stacks of them, empty ones, lined up in patterns. Something twigged in his memory—or past memory?—but he couldn’t make the connection. “General Sokka!” said Osha.

She didn’t move. A few of the randoms waved.

“This isn’t lunch.”