Chapter Text

It was the opening night of the season, and Stede wished he were anywhere else.

Well, not anywhere else.

His esteemed colleagues in the junior class were likely downing six packs at a Villanova frat house, so this beat that experience at the very least. And there was something to be said for familiarity — Stede’s accoutrement over the years had changed (fewer button-up vests and more windsor knots), but his parents’ hadn’t. His father wore tails and shoes that reflected chandelier light. His mother was draped in jewels that dragged along the floor, caught in sidewalk cracks until she yanked the train of the dress to dislodge them and sent them skidding into storm drains. Stede’s parents had their own box at the symphony — the same velvet cushions he’d sat on as a child — and tonight they climbed the stairs toward it in a dull procession. The first half was (thankfully) brief, ending with a Mozart concerto that Amadeus himself probably didn’t even like, and conducted by an apprentice who seemed liable to collapse into a puddle of sweat at any moment. The hall was packed with velvet and napkins smudged with lipstick and a cold silence that even the orchestra itself couldn’t penetrate, broken only by the sterile applause of people who took music seriously because they were meant to.

In all the years Stede had accompanied his parents to the orchestra, he saw only fleeting moments of true enjoyment among his fellow patrons. Occasionally someone would burst the seams of propriety, jump to their feet as soon as a piece was concluded and shout “bravissimo!” at the top of their lungs. Stede’s father and others like him looked upon these ne'er-do-wells with thinly-veiled contempt. Stede recognized that look. It had been leveled at him more than once, had silenced him before he had the chance to speak.

All the more perplexing was the praise the box holders would pile onto these performances, even as they frowned over crumpled programs: Incredibly moving. Riveting. Emotionally resonant. He heard the same flat accolades during intermission as he fetched his mother another glass of champagne, squeezing between loud taffeta. A rousing first half, someone said. I so agree, added a disembodied voice. Where was that reverence in their expressions? Their reactions? Because Stede didn’t see it, not in the staid responses when the conductor lowered his baton, not in the moments of crescendo where Stede felt like he might fly out of his seat right up into the rafters when everyone else seemed firmly — inexplicably — rooted to the ground. But that was his story, it seemed, a life spent puzzling over the stark difference between what he felt and what the world allowed, blank pages where color should be.

So Stede clapped along with everyone else at every concert — polite, serene — even when the music swept through him and set his heart racing. Tonight was no different. He was wearing a new tuxedo, just fetched from the tailor’s: pressed and perfect. He struggled to swallow around the tightness of the bowtie. He could see his reflection in his black Oxfords if he looked down, a faded daguerreotype. He passed the bubbling flute to his mother and sat with his back against the plush cushion of his seat, tried to mirror the angular stillness of the crowd around him. Stede sat motionless and unmoved, as if to endure the coming performance instead of relish it. This was a performance, in and of itself. Perfect placidity. Stede was a virtuoso. Even Vivaldi couldn’t break him (take that, Antonio).

Voices came close, though.

Stede saw his first choral performance by happenstance, the year after they moved from Aotearoa. He couldn’t have been more than five or six, and was tagging along with his mother as they wove through throngs of Christmas shoppers at Macy’s and the market at city hall. There was a little stage next to one of the stalls, and while Stede and his mother were waiting in line for hot chocolate, a group of carolers shuffled up in their thick coats and scarves. As they opened their music folders, one of them blew into a little metal device that he produced from his pocket (a pitch pipe, Stede would later learn). There was no conductor, no one to guide them. Just a shared breath and a tiny nod, so small Stede nearly missed it. It was as if they grabbed the first note from thin air, held it together and then in variation, spun it into a familiar tune entirely new.

Stede was transfixed — so much so that he walked straight into the person leaving the counter, spilled hot chocolate all over their wool coat and set off a loud and protracted argument between Stede’s mother and Mr. Spilled-Upon, whose very opinionated Bichon Frisé also joined the fray. The whole affair put a kibosh on the holiday cheer. But Stede never forgot hearing their first chord, the surprise and exhilaration of it. And if he had to work a little harder to tamp down his excitement during choral works in the years since, no one needed to know but him.

His parents weren’t keen on choral pieces, but on this particular night Ein Deutsches Requiem was the entirety of the second half. They couldn’t very well leave at intermission. Stede wasn’t sure what he expected — the setting was so different from the Christmas market all those years ago that he didn’t think of it.

He should have known what he was getting into. The conductor was Benjamin Hornigold — a legendary interpreter of German romanticism, and the kind of maestro that looked perpetually aggravated at the audience, the orchestra, and especially the choir. But Stede’s father touted the man as a genius, used words like “brilliant” and “electric” with as much passion as one might have reading the ingredients from a cereal box. Stede was skeptical until the orchestra began to tune for the second act. The atmosphere was charged even before Hornigold took the podium. The orchestra sat at the edge of their seats; the choir were poised like statues in the loft above. And then the conductor appeared, marched over to the center of the stage, and breathed deeply. Stede felt the hair raise on the back of his neck. His mother shuffling in the seat next to him was louder than an earthquake. When Hornigold raised his baton Stede felt a shift, like a raincloud breaking open. Then the maestro gave the downbeat.

The low pulse of the first measure was almost inaudible, a single note more felt than heard. Stede watched the violists prepare their bows, then listened as they joined the french horns in a mournful cascade that seemed to roll like gentle hills, dipping briefly to meet the steady thrum of cellos. Each instrument picked up where another left off, building inexorably toward a tremulous moment of dissonance in the strings, forte and strident, before receding like the tide. Then Hornigold raised his left hand, just slightly, and the choir inhaled together, beginning the music before a note was sung. When they entered — a capella, pianissimo — Stede thought of dawn, and the slow change from the chill of night to the warmth of day, grass unbending as dew lifted. It seemed like they were singing right to him, a hundred people on an almost-whispered chord so delicate that Stede worried the smallest movement might break it.

Selig sind, die da Leid tragen

Stede’s German was rudimentary at best, and he didn’t dare open his program for the translation lest he rustle a page. He found that he didn’t need to. He read the words in the singers’ faces, felt them translated in timbre. Mercy. Hope. Wonder. The sound almost frightened him, like the choir was voicing something forbidden. It was certainly forbidden for him. Stede studied music insofar as it was a noble academic pursuit worthy of polite conversation. He dutifully attended piano lessons despite a real lack of finger dexterity, simply because playing a duet at a dinner party would please his mother. But these singers were immersed — unabashedly so. Stede couldn’t recall a time when he’d been immersed in something and not been scorned for it.

Denn sie sollen getröstet werden

A flute began a new motif, simple quarter notes sliding above the staff and suspending there briefly before the lower voices joined it, affirmed it. Getröstet. Comforted, Stede remembered. But this wasn’t comfort offered out of pity, the kind his mother offered him when his father wouldn’t let Stede keep the stray kitten they found under the porch, or the apologetic looks of teachers who turned a blind eye to the “pranks” he was subjected to (which were probably actual crimes in hindsight) and the cruel indifference it had become. This was comfort given because the comforted were deserving of it, entitled to something other than an upheld palm that told them to stay silent. The sopranos crescendoed on a high G, and Stede felt deserving.

Die mit Tränen säen

Then a lush, full freefall into tied quarter notes, like tears smearing fresh ink. It was going to be okay, he thought — he felt. He couldn’t remember if anyone had told him that, at any time in his life.

Werden mit Freuden ernten

An exuberant march toward resolution, toward joy, led by the tenors and basses — men, Stede assumed, who were allowing the notes to move them, to lift their voices with an abandon that Stede was sure would invoke his father’s disdain. He glanced over at the man himself, who Stede could barely see behind the voluminous tufts of his mother’s skirt. Edward Bonnet looked for all the world like a disenchanted corpse, tolerating the unseemly histrionics on display at its wake. It was how Stede saw him in his mind, when asked to think of his father. It was how he was expected to behave, especially as the only son of a Bonnet patriarch. Detached, unmoved. Stede wondered where it all went, the energy that he’d been not-so-subtly told to tamp down since before he could form full sentences. Did he swallow it down? Was it waiting somewhere, like a coiled snake?

Sie gehen hin und wienen

Or was it unspooling now, as Stede sat here listening to what Hornigold conjured from the people before him? Because he could feel it building as the violas moved in rivulets of three, as the voices echoed one another: cry, cry, cry.

Und tragen edlen Sammen

Und kommen mit Freuden und brigen ihre Garben

The sopranos led a charge up the staff, asking the other voices to follow. And Stede felt suddenly desperate, like he had to decide what path his life should take before the next note arrived. He felt as if the box they sat in would collapse, scrap paper crumpled and tossed, inescapable. Freuden was tinged with the same hysteria that Stede sometimes woke up with in the middle of the night, his chest burning. I have to get out, he thought. How do I get out?

Selig sind, die da Leid tragen

Denn sie sollen getröstet werden

The opening chords returned, this time with a steady beat from the cellos that Stede felt beneath his feet. This comfort was a demand, emphatic, perhaps the last opportunity for Stede to reach out and take it. Sollen swelled on a suspension held across the voices and the instruments, and it’s what finally made Stede grip the armrests of his chair for dear life, like he might run either onto the stage or out of the theatre screaming at the top of his lungs. The world seemed to hinge on that word, a coin that could flip and land him mired in expectation or lifted to some new possibility. Getröstet werden floated above plucked harp strings as the flutes resolved the piece on A and F, sustained in gentle polyphony. The choir had stopped singing, but Stede still heard them, somehow, felt them spinning up into the high rafters and out into the night.

Hornigold’s baton stayed aloft, as if it held the memory of all the music it had evoked, all the music still to come. Stede felt his heart beating fast. Everyone knew you weren’t meant to applaud between movements, and Hornigold would give the downbeat for the next one at any moment. But Stede was clapping before he could stop himself, was halfway out of his seat and nearly raised his hands higher before his father reached across a shocked Mrs. Bonnet and gripped Stede’s forearm tight.

“Be silent,” Stede’s father said. His grasp had the weight of years behind it.

Selig sind, die da Leid tragen

Stede could feel eyes on him, could hear faint whispers that felt like thunder. Stede sat without a word, pushed his hands into his knees. The moment should have been utterly and completely mortifying. But there was a thrill that buzzed beneath his skin, simmering there at low volume. Stede wondered what would happen if he cultivated it, drew it out to forte in a major key. He wondered if, one day, he might stay standing.

Notes:

Music from this chapter:

First movement of the Brahms Requiem.

This piece took my breath away when I sang it for the first time, and it remains my all-time favorite Requiem mass. It will be the centerpiece for this fic!

Chapter 2: Intermezzo

Notes:

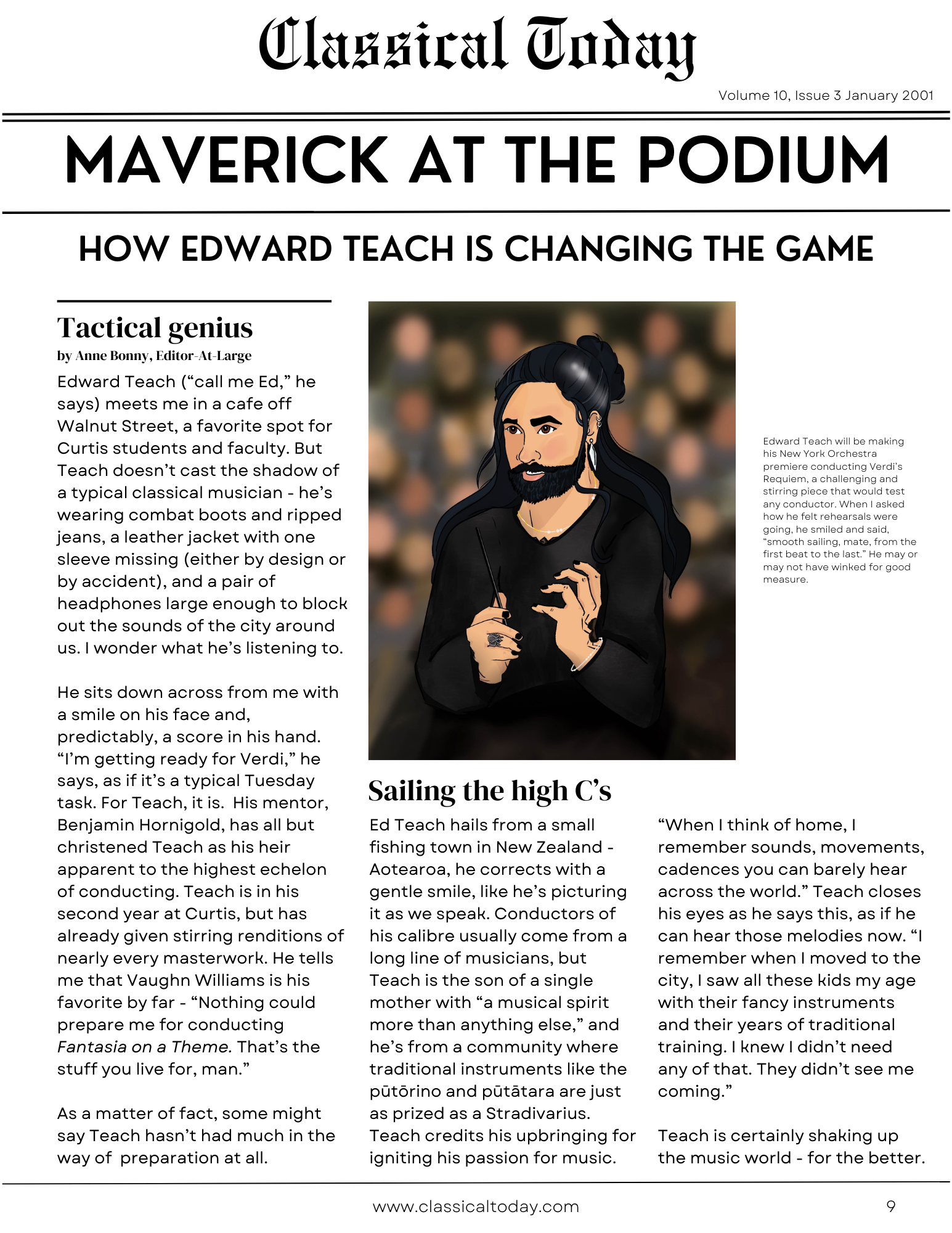

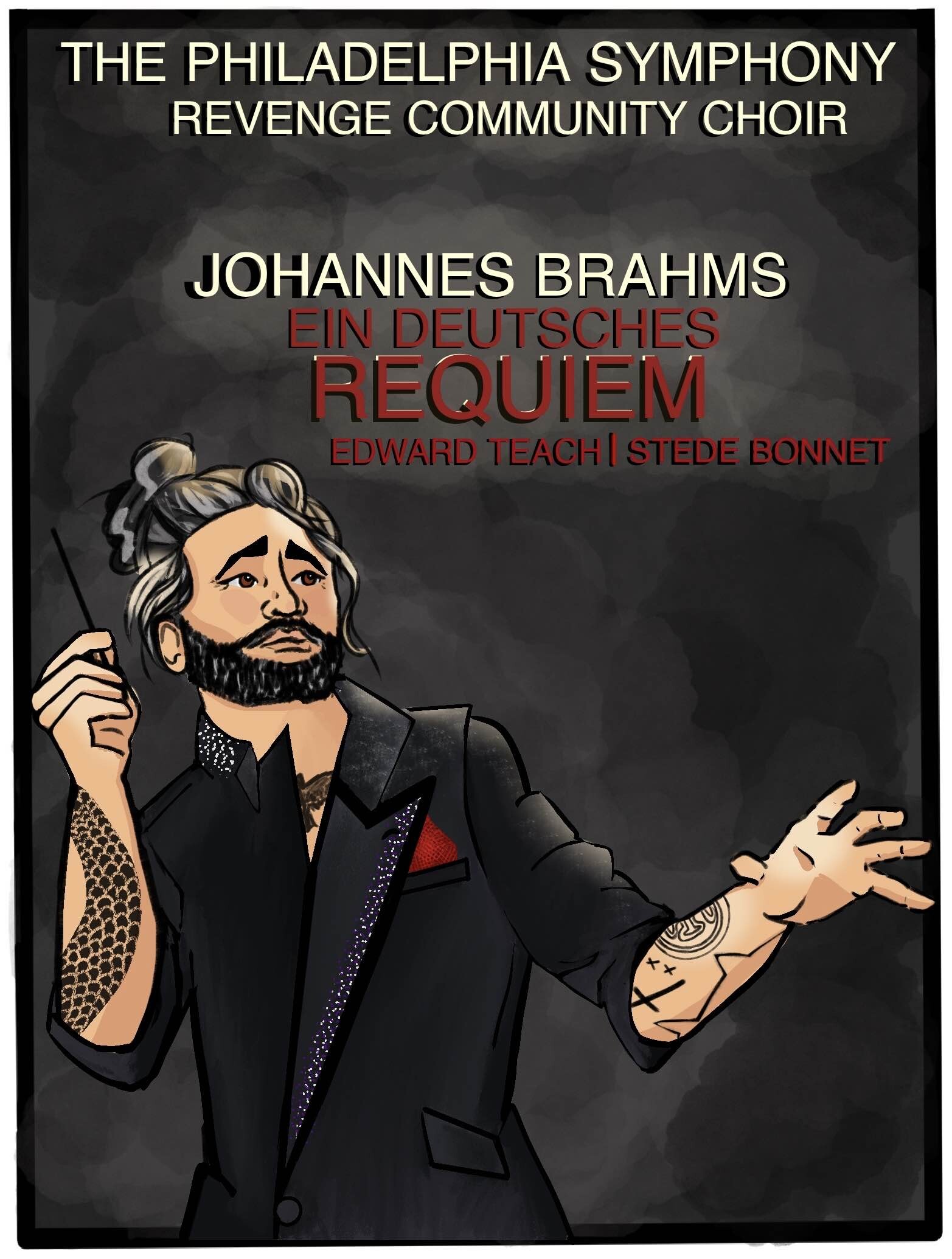

Look at him! It's young conductor Ed! I can't thank Gemma enough for this beautiful art.

(See the end of the chapter for more notes.)

Chapter Text

Article text:

Maverick at the Podium: How Edward Teach is Changing the Game

Tactical Genius by Anne Bonny, Editor-At-Large

Edward Teach (“call me Ed,” he says) meets me in a cafe off Walnut Street, a favorite spot for Curtis students and faculty. But Teach doesn’t cast the shadow of a typical classical musician - he’s wearing combat boots and ripped jeans, a leather jacket with one sleeve missing (either by design or by accident), and a pair of headphones large enough to block out the sounds of the city around us. I wonder what he’s listening to.

He sits down across from me with a smile on his face and, predictably, a score in his hand. “I’m getting ready for Verdi,” he says, as if it’s a typical Tuesday task. For Teach, it is. His mentor, Benjamin Hornigold, has all but christened Teach as his heir apparent to the highest echelon of conducting. Teach is in his second year at Curtis, but has already given stirring renditions of nearly every masterwork. He tells me that Vaughn Williams is his favorite by far - “Nothing could prepare me for conducting Fantasia on a Theme. That’s the stuff you live for, man.”

As a matter of fact, some might say Teach hasn’t had much in the way of preparation at all.

Sailing the high C’s

Ed Teach hails from a small fishing town in New Zealand -Aotearoa, he corrects with a gentle smile, like he’s picturing it as we speak. Conductors of his calibre usually come from a long line of musicians, but Teach is the son of a single mother with “a musical spirit more than anything else,” and he’s from a community where traditional instruments like the pūtōrino and pūtātara are just as prized as a Stradivarius. Teach credits his upbringing for igniting his passion for music.

" When I think of home, I remember sounds, movements, cadences you can barely hear across the world.” Teach closes his eyes as he says this, as if he can hear those melodies now. “I remember when I moved to the city, I saw all these kids my age with their fancy instruments and their years of traditional training. I knew I didn’t need any of that. They didn’t see me coming.”

Teach is certainly shaking up the music world - for the better.

Box next to image: Edward Teach will be making his New York Orchestra premiere conducting Verdi’s Requiem, a challenging and stirring piece that would test any conductor. When I asked how he felt rehearsals were going, he smiled and said, “smooth sailing, mate, from the first beat to the last.” He may or may not have winked for good measure.

Notes:

Fun fact! "Dies Irae" from Verdi's Requiem is the piece that introduces us to Blackbeard in OFMD season 1. Listen to this rendition conducted by Yannick Nézet-Séguin, one of the major inspirations for Ed's character in this story.

Chapter Text

Lucius was late, and Oluwande had to dash off to the printer to pick up the correct version of the piece for tonight, and Buttons was nowhere to be found (as usual), so Stede was stuck setting up the chairs on his own. These were the fancy chairs — there was padding on the backs of them, and the seat cushions were pleasantly firm — but their ergonomic wonders came at a (literally) heavy price. They were also impossible to unfold without performing a series of maneuvers that threatened to throw Stede’s back out on more than one occasion. Who knew — maybe today would be his lucky day.

He was about fifty chairs in, with at least twenty more to go before he could expect any help. The school secretary watched from her perch at the front desk, totally able but unwilling to help. Stede’s choir had been renting this rehearsal space for years, and he could count the number of words she’d spoken to him on one hand.

There was a rap at the door, followed by the unmistakable sound of someone repeatedly jamming the silver bar to open it.

“Dolores!” Stede shouted, knee-deep in chairs. “Can you prop the door open?” Dolores looked at Stede as if he’d just asked her to part the Red Sea. She raised an eyebrow and promptly bent over her desk to scribble on a piece of paper. “Heaven’s sake,” Stede mumbled, propping a chair against the wall. It slid to the ground with a mighty crash, and Stede didn’t acknowledge Dolores’ outraged tsk as he scrambled to the front door.

He could see Oluwande standing on the other side, a box in his arms that tipped precariously when Olu shoulders through the entryway. “Thanks mate,” said Olu. “Should be all sorted with these.”

“I should hope so,” Stede said. “Who orders the Barber version of Sure on This Shining Night? I mean really.”

“Yeah, bollocks to Samuel Barber.”

“Well now, let’s not be too hasty. His Adagio for Strings is an unmitigated masterpiece.”

“Stede, I was kidding,” said Olu. “Proper Barber stan, me.”

“Oh, of course!” Stede said as he held the door. Olu laughed under his breath — the kind of laugh that made Stede return it: convivial, fond, lighthearted. He remembered a time when laughter like that was hard to come by in the company he kept.

“Hey Dolores,” Olu called as they passed the front desk.

“Hello Mr. Boodhari,” Dolores said, all sweetness. Stede wasn’t sure if he should be jealous of Dolores’ clear preference for his Assistant Conductor, but he suspected she would have been more than happy to lend a hand if it were Olu setting up the chairs tonight.

“What did you do to win her over?” Stede whispered as they walked to the practice room. Olu set the box of music down on the stage, started unpacking it with practiced hands.

“I just smile at her, mate,” Olu said with a shrug.

“I smile at her,” Stede pouted, and Olu laughed again.

“Maybe she’s intimidated by you. You’re the big maestro.”

“I highly doubt that. Sometimes I even have a hard time believing that I’m the maestro at all, even after all this time.”

“Well, I’m glad you are,” Olu said seriously. He gave Stede one of those grins that he seemed to reserve for quiet moments between the two of them — a notation they agreed on, a musical phrase they both loved. This was only Olu’s second season with Revenge Community Choir, but he was (happily for Dolores) indispensable.

Olu placed the last piece of music on the pile he’d made, scooped up the empty box and started breaking it down. “I’ll go prop open the door,” he said, but as he trotted over to the entrance Dolores rose from her chair and slipped the umbrella stand in the door frame.

“Really?” Stede muttered, wrestling with a particularly ornery chair.

A gaggle of sopranos trickled in a few minutes later — all inexplicably named Roberta, save one — and immediately berated Stede for not putting enough space between seats.

“You should have Lucius do it,” said Roberta, dragging her chair half an inch to the left with as much fuss as possible. “He always gets the spacing right.”

“You’ll have to make do with my poor attempt tonight, ladies,” Stede said, unfolding the last of the chairs and plopping it loudly in the tenor section.

The Robertas tutted amongst themselves, and the lone Agnes shuffled to the front of the room to fiddle endlessly with the thermostat.

“Hey, where’s Buttons?” Olu said as he walked back into the room. “Rehearsal starts in twenty minutes.”

As if on cue, the man himself emerged from the back of the stage and solemnly walked to the piano at its center. He sat on the bench, looking for all the world like he was waiting for a bus. He placed his hands on the keys and sat stock still.

“Buttons,” Stede called, waving a hand for good measure. “We’ve got some time. No need to get settled in just yet.”

“My mistress calls me in her due time,” said Buttons. “I am prepared to accompany ye, cap’n.”

“Alright, Buttons?” Olu joined Stede in the center aisle and leaned in close. “Who’s his mistress again?”

“I think it’s music? Like, the concept?”

“Right,” said Olu, and handed Stede a paper seating chart with a few new names scribbled in along the edges. “Wasn’t sure where you wanted to put the new folks, so I have them in the first two rows of their sections.”

“That’s perfect, thank you Olu.” Stede scanned the names, briefly recalled each of their audition pieces. Voi che sapete for one, The Wild Rover for another. Stede loved hearing new singers. He always felt intensely privileged on those occasions, more than he ever had in the Bonnet symphony box or in the halls of Yale. He still wasn’t sure that he deserved the trust that singers placed in him — because that’s what it required, he realized. It was one thing to sing Happy Birthday at a party or grab the microphone to join in for “Wanna Be” at karaoke. It was something entirely different to stand in front of a panel of people — of strangers — and ask them to listen to this central sound (the one that curled inside your chest and simmered there, surprised you the first time you heard it ring out into the world) and judge it according to its merits.

At first Stede didn’t say no to anyone who auditioned, and he didn’t really need to — people weren’t exactly lining up to audition for the passion project of an unknown conductor — but word of Stede’s…unique choral philosophies spread quickly in the relatively small (and shrinking) Philadelphia choir scene, which until then had mostly consisted of semi-professional groups with cutthroat audition protocols and an unspoken rule that only people with classical training need apply. Musical chops like sight reading were well and good, but Stede believed that technique and theory could be taught — they’d been taught to him, after all, and he often doubted his innate musicality. Stede had experienced enough gatekeeping in his life to resent it, and it was the last thing he wanted to do with singing. But Revenge’s growing popularity over the years meant that Stede had to draw a line somewhere. It turns out you can only have so many sopranos in one room before things start to get unwieldy.

Stede felt each rejection in his solar plexus, right under his ribs. Maybe it struck close to home, reminded him of the times when he’d been made to feel unwanted — countless occasions that had (thankfully) become few and far between, but were bitter enough for the taste to stick. But it was more than that. Each “no” he delivered seemed like a betrayal, somehow, like Stede was withholding a gift he had no right to bestow. He’d found his place in music, hadn’t he? Who was he to close that door for someone else?

He followed up each rejection with sincere compliments and suggestions for other singing opportunities, including a non-performing community singing group called Crew of the Revenge that Olu lead on Saturdays, where folks could gather with old scores from their attics and sing along to cassette recordings of Eugene Ormandy, or try their hand at new harmonies, or knit in the corner and hum along just to feel the music close around them. Stede stopped by Crew meetings every once in a while and always left feeling filled to the brim, like he might overflow and cartwheel down the street. He wondered if having such a place in those early days might have turned the lonely ache down just a tad, enough for him to avoid a useless stint at Penn Law and an engagement that was never going to work for many reasons. It might have eased the way, if nothing else. But Stede couldn’t — and didn’t — regret where his circuitous route took him, where he ended up. Where he might yet venture.

“Finally,” said Olu beside him. Stede followed the man’s gaze to the front door, where Lucius was shooing a hapless tenor out of the way with an overstuffed black binder.

“Lucius, where have you been? The singers are —”

“Oh my god,” Lucius wheezed, throwing his music on the closest chair. “I just got off the phone with Jeffrey. You know, from the Broad Street Chorale.”

“Ah yes, Jeffrey! Fettering! Lovely guy, how is he?”

“You were talking on the phone?” Olu said, eyebrows raised almost under his beanie. “Sounds serious.”

Lucius gestured for Olu and Stede to follow him up the stairs to the stage, hurried back behind the curtain with an impatient wave of his hand. Stede couldn’t remember seeing Lucius this worked up about anything, save the day Roach’s forty-orange cake (and not Lucius’ lemon zest bars) was the clear favorite at the after-concert reception. “Everything alright?”

“They’re disbanding,” said Lucius in a harsh whisper.

“Who is?” Stede asked.

Lucius rolled his eyes, but Stede could tell his heart wasn’t in it. Hoist the red flags. “Who do you think? The Chorale.”

“You’re not serious,” said Olu, and Stede felt his stomach drop. He knew Olu had sung with them for years, apprenticed there right out of Temple.

“Please tell me it wasn’t —”

“Oh, it was,” said Lucius. Olu cursed under his breath. The Chorale was a paid roster of singers who had been fighting to unionize ever since the pandemic, touting the apparently controversial opinion that musicians deserve fair wages and benefits for their work. Stede wished he were surprised that their efforts had ended this way.

When Stede came back to Philly after his doctorate, there were at least a dozen choirs of every shape and size — large symphony chorales and a capella groups, a gay men’s chorus and a feminist singing group, several semi-professional community choruses, a bell choir (technically a choir!). There was no shortage of options for the aspiring singer. Or bell player, Stede supposed. A “golden age of choristry,” he used to say. But funding for the arts — like everything else — had been dwindling over the years, and the pandemic was the proverbial nail in many groups’ coffins.

“Some of our section leaders are Broad Street folks,” Olu said. “Chances are they’re going to know about this and start talking as soon as they arrive.”

“For sure,” agreed Lucius. “One thing about singers, they’re talkers first.”

“I’ll make an announcement,” Stede said solemnly. “Do you think Jeffrey would mind? Poor fellow.”

“Stede,” Lucius said. “He knows we rehearse on Wednesdays. There’s a reason he called me. The bigger the stir, the more their board will hear about it.”

Stede could hear the room beyond the curtain filling up, chairs scraping across the floor and music shuffling, an errant Roberta shouting for the seating chart. His choir produced some of the loveliest sounds in the world — tremulous pianissimos and full unison chords — but this was perhaps his favorite: the footsteps and greetings and chatter of dozens of people from all over the city, from every conceivable walk of life, arriving to sing together. He let himself listen to the procession for a few seconds, breathing deep.

“Better get to it,” Olu said. He turned on his heel and walked across the stage, offered a few “hello’s” that sounded cheerful enough to the unassuming ear.

“Sorry to be the bearer of bad news,” said Lucius. He stepped forward and held the curtain for Stede — a gesture so rare that Stede nearly did a double take. Stede had known Lucius for long enough to see through the prickly exterior and feigned nonchalance (although there was absolutely some legitimate nonchalance going on there, no question). But Lucius cared about Revenge as much as Stede and Olu did, of that Stede was sure.

Stede offered him a small smile, moved closer to pat him lightly on the shoulder. “I’m glad I heard it from you instead of a singer,” he said, but then balked at his oversight. “Of course you are a singer, but, you know.”

“I’m a singer under duress, Stede. Especially now that you have me on tenor one.”

“We’re in desperate need, Lucius! Those high G’s aren’t going to sing themselves!” Stede said as they walked out past the piano.

Olu was waiting for him by the podium as the section leaders passed out the new music. Poor Frenchie was doing his level best to instruct people how to pass the scores down to the end of their rows — a straightforward task made needlessly complicated by the confounding opinions of at least one person in every section.

“We should start with the middle of the row, Frenchie,” said Pete, standing and reaching over his fellow basses. “Here, give me the stack.”

“Don’t take away his moment, man, let him pass out the music,” said a new singer across the aisle in the alto section. It took Stede a minute, but then he remembered — lovely, rich mezzo tone, interesting name (Jim Jimenez, Stede recalled), and an air of quiet mystery that only altos seemed able to muster.

Pete practically guffawed. “Excuse me? Who even are you?”

“Now Pete!” called Stede from the stage. “Let’s make sure our new singers receive a warm welcome, shall we?”

“Shouldn’t even be next to the altos, I’m not in the right section,” Pete muttered as he sat back down, renewing his perennial complaint that Stede couldn’t appreciate his “Pavarotti resonance” and place him next to Lucius and the other tenor ones.

“I’m just doing my best, mate,” said Frenchie, who handed off the rest of the music and raised his arms as if to wash his hands of the whole affair.

“Alright singers,” Stede said with a clap of his hands. Ninety-odd faces turned to look at him (not many absences tonight, huzzah!), and Stede let his eyes wander over the crowd to acknowledge each of them. “Let’s all stand and warm up while you get your music sorted. G major please, Buttons.”

Buttons dutifully played the chord as Stede demonstrated an arpeggio on “mi me ma mo mu,” adding an upward twirl of his wrist as he connected the top and bottom notes of the scale. The choir joined in on cue, a wall of sound that seemed discordant at first but smoothed and stabilized as the voices settled in, as they began to hear each other. Stede always pictured it like birds landing on a lake from a height, sending ripples out across the surface as they tossed their feathers before drifting forward on calm water. He pointed up, and Buttons played the next whole step as Stede gestured for the singers to follow. The choir never took long to find their sound together — by the second or third scale they started breathing together, listening, even subconsciously. He stopped them once, asked them to consider vowel placement on the “mo” (a near-constant challenge with Philadelphia accents), then took them back down again at varying tempos and dynamic cues (“watch” he mouthed, chuckling when someone barged in on forte when he signaled for mezzo piano).

This was one of his favorite parts, before they cracked open a single piece of written music. He knew some conductors relished the power they felt in these moments, leading a group of people without saying a word, with just the tips of your fingers. There was some of that, sure. But what he loved most was the trust they placed in him — him, he still thought with wonder — that they allowed him the privilege of guiding them.

Stede led them through a few more exercises, shrugging with bemusement as Buttons added completely unnecessary and delightful flourishes to the warm-up chords — there was no stopping the man once he really got going. He gestured for everyone to sit after the warm up and stepped in front of the podium.

“Thank you everyone, and we’ll begin in just a moment. I know we usually save announcements for the break, but given that quite a few of you might already know this news I thought I’d take some time up top to talk about it together.” A few of the section leaders shared knowing glances, and Stede could hear a few whispers from the back rows. “As some of you may have heard, the Broad Street Chorale is disbanding.”

The errant whispers became a fully-voiced murmur, and several singers took out their phones as if to check with outside sources. “That’s awful,” said one of the Robertas, but in a way that made Stede wonder if she was secretly enjoying the hullabaloo.

“When is this happening?” asked new singer Jim. “Is it effective immediately?”

“I’m not entirely sure,” Stede admitted. “But my understanding is that they will be cancelling all future engagements as of today. Do I have that right, Lucius?”

Lucius gave a thumbs up from his seat in the tenor section, but then added, “Thumbs up as in ‘yes,’ not, like, a thumbs up of the situation.”

“Why are they disbanding?” asked the Swede, a singer who’d been with Revenge for at least five years but whose actual name Stede still, inexplicably, did not know. “I didn’t think they had a band?”

“Oh my god,” said Pete.

“I understand,” Stede said, putting his hands up to ask for quiet. Those who had been talking amongst themselves or checking their phones turned to him. “I understand that this comes as a shock. It’s very upsetting. And I know some of you were members of the BSC. I’m so sorry this has happened. My door is always open if you ever want to talk.”

Frenchie raised his hand, then slowly rose to his feet when Stede nodded at him. “The writing was on the wall, wasn’t it?” he said. “We were trying to look out for each other, and look where it got us.”

Stede turned slightly to catch Olu’s gaze, raised an eyebrow and nodded his head a bit when Olu returned it. “We don’t know if this decision is based on the BSC members’ attempts to unionize,” Olu said, garnering an accompanying scoff or two from the choir. “I certainly hope that isn’t the case. But no matter what the reason, Stede and I want you to know that we are doing everything in our power to make sure Revenge has a secure future. We are absolutely committed to that. Aren’t we, Stede?”

Olu was a passionate man — Stede knew that. He saw it in his conducting, in the care with which he chose and interpreted pieces for the programs he led. But if Stede was the high-strung perfectionist of the two of them, Olu was the laid-back improviser, going with the moment with a smile on his face. Stede envied that about him, and appreciated it more than he could say. Right now, though, Olu wasn’t evincing his usual unflustered joviality. This was steely determination, and maybe a little anger, and a resolve that made Stede want to rush over and hug the man for caring so much.

“Olu is absolutely right,” Stede said, looking back out at the choir. Stede knew that Revenge was a safe haven for many of the singers — heaven knows it was for him. Wednesday nights were sacrosanct, a time for each of them to set aside the uncertainty that ran riot in the outside world and give their full attention to the notes in front of them, some of which had been transcribed before anyone in the room was born or thought of, before any of the things that scared or challenged them existed. There had been a lot of hand-wringing among his fellow musicians lately — it’s a tough time for the arts and who knows what will happen were the common refrains. Both of those things might be (and likely were) true. Stede owed it to this group of people to fight for their choir, for this space that gave them solace and stirred up joy.

“How much more jabbering should we expect before we get to the music, cap’n?” said Buttons, who seemed to be shaking with the effort of keeping his fingers still.

“Rude,” muttered Pete.

“Buttons is quite right!” Stede said as he opened his music. “What better way to demonstrate our commitment than to start preparing for our next concert? I believe many of you have sung this —”

“I sang this under Robert Shaw,” said one of the Robertas.

“It was released after his death, Roberta,” quipped Lucius, who Stede knew considered this particular Roberta his personal nemesis.

“In that case, let’s read this once through, shall we?” Stede said, offering Lucius a raised eyebrow of reproach.

Olu moved from the side of the stage to join the basses, and Stede waited for the chorus of shuffling papers to diminish before turning to Buttons and giving the downbeat. The opening chord was centered on a low D, hovered there before shifting into slurred eighths in a simple cascade on the treble clef. Buttons played it as if he were giving a recital at Carnegie Hall, leaning into the notes like each one was precious, like each needed to be placed just so. Stede watched some of the singers shift in their seats, moving instinctively with each new phrase. Then Buttons played the melody, the high note like a struck bell. He looked at Stede, who showed him a slight ritard in common time — easy, Stede asked with an outstretched hand, let it build — before nodding on the next downbeat.

The lower voices entered on a unison chord, the rhythm steady and sure, like each person was telling their own story.

Sure on this shining night of starmade shadows round

Kindness must watch for me this side the ground

An eighth lift, long enough to blink up at the sky.

On this shining night, this shining night

Slurred eighths returned, then a stretch on “shining” that Stede brought up just slightly, piano to mezzo piano — it’s okay, he said with a raised palm, it’s okay to feel this — and then the clear, lovely D flat sustained on the second phrase — shining, shining — like the tenors and basses might hold it forever. It didn’t matter how many times Stede heard this, how many times he conducted it. It plucked right under his ribs, coaxing his heartbeat faster — Prometheus if the eagle were a friend. He’d defied many things to get here, he supposes, expectations that almost closed around him tight enough to choke. He remembered starless nights when none of this seemed possible. It made the note soar.

Sure on this shining night of starmade shadows round

Kindness much watch for me this side the ground

On this shining night, this shining night

The sopranos and altos took up the melody, the tenors echoing on descant. And this is where the magic happened, Stede thought, as he cued the bass entrance. It shouldn’t be possible, that close to a hundred voices should sound like they were meant for this very moment, to weave this particular set of notes together and land on “shining” like a promise. Mary once told him that Stede was the most pessimistic optimist that she’d ever met. “You’re like an unstoppable beam of positivity, Stede, but you’re always surprised when things work out for the best.” She was right, of course — about most things — and this was a testament to it. He was taken aback every single time, even after fifteen years of conducting. How can they do this ? He thought. How can they look at marks on a page and make this ?

The accompaniment changed, introduced a new counterpoint. Bright, tremulous. Buttons seemed lost in it. Stede motioned for the tenors and basses to breathe, inhaled with them as they prepared for the A flat.

The late year lies down the north

All is healed

All is health

Oh, and that healed . Suspensions like this always felt seismic, but this one carried on a true crescendo, no breath into the next phrase. Stede watched as a few of the singers closed their eyes — how can’t you? He wondered, even as he spurred them on. He always marveled that this assortment of lower voices embraced these moments shamelessly — basses who were choir veterans of thirty years or more, men who lived in the suburbs and watched the Eagles on Sundays, tenors with delicate tattoos, others still in scrubs from a shift at the hospital. Stede always wondered how his own father got it so wrong, how he didn’t see (didn’t want to, more like) the possible ways of being for humans in general and Stede in particular. For a few years Stede was convinced it was malice, plain and simple. His father never hid the fact that he disapproved of Stede’s interests, his ideas, his…well, just him , at the end of the day. Lately he wondered if comprehension was something he was incapable of altogether, at least about anything other than interest-yielding accounts or the course ratings of Main Line country clubs. It didn’t excuse it, but maybe it explained it. He was sure his father never heard something like this, or at least could never interpret it — the voices of people who weren’t looking over their shoulder for the derision (or worse, indifference) creeping up behind them. Just unapologetic, unfettered sound.

High summer holds the earth

Hearts all whole

Stede made a mental note to add a breath mark between “earth” and “hearts,” the slightest pause to affirm the ending, or at least aspire to it. It was near impossible to fill your heart these days, Stede thought. The closest he came was in these moments.

The late year lies down the north

All is healed

All is health

High summer holds the earth

Hearts all whole

Sopranos and altos joined, both rising above the staff on the second “all” — “yes, altos!” he mouthed, and even the rolled eyes he received seemed fond. Altos were historically his toughest crowd. If he tried, he could pick out some of their individual voices, especially on the dissonance when they split in the four/four measure. “Crunchy,” Olu called it, the delightful phrases when the notes were so close together that they were almost smudges, like they might collide if left to their own devices. He could tell the altos loved to sing them, leaned closer to one another to really hear the other part alongside theirs. Maybe it was too literal a translation, but: differences sound great, actually. More of that, please. It was a lesson hard learned in the Bonnet household.

And here. Here it was.

Sure on this shining night

Ritard, swell, crescendo. The entire choir braced for it, almost shimmered with it. Now the dissonance marched toward the final resolution, an ecstatic forte. Unison, then polyphony.

Sure on this shining night

Big breath. Brand new harmonies, like revelations. God, was there a time when Stede didn’t have this? He knew there was. It didn’t seem possible now.

Sure on this shining night

The sopranos arrived at the highest note in the piece, a high A flat that brushed the clouds. They could sing higher — the Robertas reminded him of that on every occasion — but in this music it was like grabbing stardust, like a sudden lift from Earth. He caught Olu’s eye as he conducted the fortissimo, and it was as if they were huddled together over a brand new score, discovering it together. This was something else that seemed elusive when Stede was growing up, this unspoken connection with other people about a shared joy.

I weep for wonder wand’ring far alone

Buttons played delicately here, as if he might otherwise disturb the singers. The altos and basses sustained on “weep,” low in their registers, as the other voices completed the phrase. Somehow it was the most evocative of the entire piece, at least for Stede. He could picture what was likely intended — someone walking in the wilderness, the black sky above dotted with stars. But he also pictured himself hearing certain melodic lines for the first time — sometimes from open car windows, or the tinny sound of his headphones, or with full orchestral and choral accompaniment — and feeling like he was the only person in the world who could hear it, the rare type of alone that felt expansive, connected.

Of shadows on the stars

And Stede loved this juxtaposition, when one of the parts moved along the staff as the others held steady around it. This time the sopranos moved in flowing eighths and quarters, ending on a chord held across the choir that reminded Stede of turning to the final page of a book you love, the ache that comes with the closing words and the blank space beneath them.

Sure on this shining night of starmade shadows round

Kindness much watch for me this side the ground

The basses were alone on the opening melody as “sure on this shining night” echoed around them in staggered entrances. Stede had held out this long, and he made a Herculean effort not to cry during rehearsal after he learned that the singers were taking bets about it in their group chat. He couldn’t stop it now. Maybe it was because he himself was a bass, had sung this very line before in one of his first programs at Westminster. Lucky, he thought as he slowed his movements, made them smaller to bring the choir down to their softest dynamic. We’re so lucky.

On this shining night, this shining night

Sure on this shining night.

A single note on a diminuendo that Stede let fade outside of rhythm, a piano chord that resolved low and hushed, like soft footsteps. Stede lowered his hands almost in slow motion, felt the choir exhale as his fingers landed on the podium. There was something remarkable about each rehearsal, Stede thought, some great choice the singers made or a note they followed especially well. But beyond that, there were certain pieces — like this one — that seemed to appear fully formed in the room, like it was waiting for this particular group of people to draw it down from the musical ether and give it life.

Stede regarded his choir with a small smile. “I’ll take that,” he said, clearing his throat. “I’ll take that any day.” Stede wasn’t sure who started applauding — probably Olu, although to his surprise Pete was clapping the loudest — but it was a burst of energy that none of them could contain, directed at no one and everyone. Stede joined them as he wiped tears from his eyes. He caught Frenchie holding a hand out to another section letter, and Stede could have sworn he heard him say “pay up.” It made Stede laugh with his whole chest.

They went over a few notes, a few simple markings, but Stede didn’t want to touch it again tonight, not after that. He wanted them to absorb that rendition, let it settle into muscle and thought and bone. They sang through a few other works for the rest of rehearsal, with a painstaking interlude spent stumbling through pronunciation for a Poulenc piece that Stede probably could have cut from the program, in retrospect.

“Frenchie, care to confirm this for us?” Stede called after at least a dozen people had an opinion about “d'autres cailloux.” “Maybe say it slowly so we can repeat?”

“Oh, I’m not French, mate,” said Frenchie with a shrug that seemed to suggest that that fact was obvious.

“Right,” Stede said, and settled on the option that appeared to cause the least distress among the peanut gallery.

He made it a point to check in with the singers he knew were members of the BSC during the break, encouraged the new singers to mingle and for the veterans to “talk to at least one new person!” One of the joining tenors made the mistake of attempting to greet Dolores, whose withering gaze Stede knew took hours to shake. Stede let the tenors and basses go home a few minutes early to rehearse a Barnwell piece with the sopranos and altos, but just as they started to get into the groove Dolores appeared on the stage with her purse over her elbow, her free arm outstretched to show Stede her watch.

“I suppose it’s about that time, isn’t it friends?” Stede said. “Wonderful work on this, we’ll come back to it next week!” He, Lucius, and Olu helped the sopranos and altos fold up the chairs, waved them goodbye as they all dispersed into the parking lot.

Jim — the new alto — was the last to exit, and stopped on their way out the door. “Hey,” they said to Stede. “Great rehearsal tonight, man.”

“Oh!” he replied. Jim chuckled and shook their head, then let the door close behind them. Stede turned to Lucius and Olu, who looked — as ever — amused in advance at whatever he was about to say. “Do you think they really meant that?”

“Jim doesn’t really strike me as the effusive type,” Olu said, flicking off the light switch in the rehearsal room. “Take the compliment, Stede. It was a great rehearsal.”

“It was alright,” Lucius added. In Lucius speak that was a rave review.

“My dog is waiting for me,” said Dolores, jangling her keys impatiently.

“Yes yes!” said Stede. He ushered Olu and Lucius out onto the pavement, bid Dolores a friendly farewell that she did not return. By the time he got to his bike Stede could feel the exhaustion practically smack up upside the head — rehearsals were as close to workouts as Stede got these days, a whole body exercise that took every ounce of whatever energy he had left after a full day of teaching. “See you next week, gentlemen,” he called to Olu and Lucius. He accompanied it with two quick rings on his bell.

“Put your helmet on, Stede!” Lucius shouted back before piling into the passenger seat of Olu’s car. Olu laughed, gently beeped the horn in goodbye as Stede pulled out onto the road with his helmet on, thank you very much.

The ride home was surprisingly chilly, enough that Stede felt his cheeks redden in the wind, felt the tips of his fingers go a bit numb. He rode down Washington Street, up 21st where he seemed to catch every red light. He was tired, but he never tired of this, a route he’d taken for years every Wednesday night. The way home.

Stede felt his phone buzz in his back pocket as he pulled up to the curb in front of his apartment building — Mary, he assumed. They had dinner plans tomorrow. He carried his bike up the steps and through the front door, parked it in its usual spot in the entryway. She’d probably want to try that new place on Walnut — she’d been trying to lure him there for weeks. He pulled out his phone, tapped his message icon.

Lucius: Stede! Check your email!

Decidedly not Mary. And, after today’s news, decidedly panic-inducing. Stede was almost positive the board wouldn’t blindside him like this — certainly not without a conversation first. His hands shook slightly as he opened his email.

The Philadelphia Symphony. Odd.

And odder still:

Mr. Bonnet,

The Broad Street Chorale was set to join The Philadelphia Symphony for the season-opening performance of Ein Deutches Requiem by Johannes Brahms. Given their dissolution, we are reaching out to gauge your choir’s interest in singing with our orchestra.

Stede’s jaw — quite literally — dropped. He might have managed to pick it back up again had he not read onto the next line:

We are pleased to share that the piece will be led by world-renowned conductor Edward Teach.

Stede’s phone went clattering to the floor.

Notes:

Music from this chapter:

Sure on This Shining Night by Morten Lauridsen. This conductor's technique is similar to how I imagine Stede's to be!

I have a bootleg version of a group of us from my choir practicing this piece - audio is not great, but definitely gives rehearsal vibes if you’d like to give it a listen here. It’s absolutely one of my favorite pieces to sing 🥹

Chapter 4: Intermezzo

Chapter by ferventrabbit

Chapter Text

Email text:

Email 1

Subject: Revenge Community Choir Performance Request

From: [email protected]

Cc: [email protected]; [email protected]

Mr. Bonnet,

The Broad Street Chorale was set to join The Philadelphia Symphony for the season-opening performance of Ein Deutches Requiem by Johannes Brahms. Given their dissolution, we are reaching out to gauge your choir's interest and availability in singing with our orchestra.

We are pleased to share that the piece will be led by world-renowned conductor Edward Teach.

Please confirm your choir's interest and availability in singing this piece on June 3rd. Please let us know by COB Friday.

Sincerely,

Geraldo (he/him)

Symphony Guest Liaison

Email 2

Subject: Fw: Revenge Community Choir Performance Request

From: [email protected]

To: [email protected]; [email protected]

Cc:

OLU AND LUCIUS DID YOU SEE THIS

Email 3

Subject: Fw: Revenge Community Choir Performance Request

From: [email protected]

To: [email protected]; [email protected]

Cc:

Hi Stede,

Yeah we were on the initial email. Exciting :-)

Olu

Sent from my iPhone

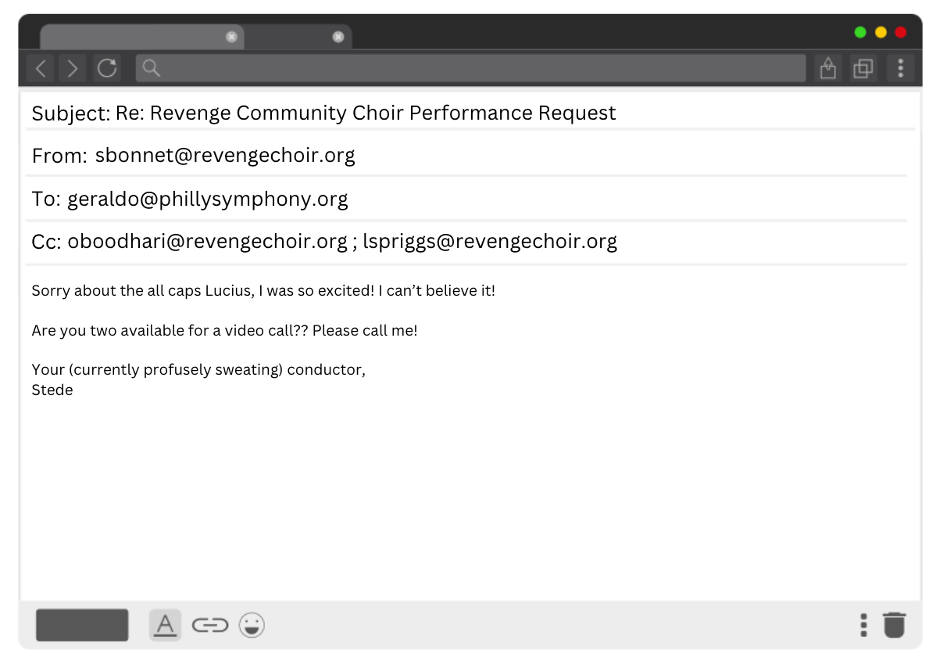

Email 4

Subject: Re: Revenge Community Choir Performance Request

From: [email protected]

Cc: [email protected]; [email protected]

Sorry about the all caps Lucius, I was so excited! I can't believe it!

Are you two available for a video call?? Please call me!

Your (currently profusely sweating) conductor,

Stede

Email 5

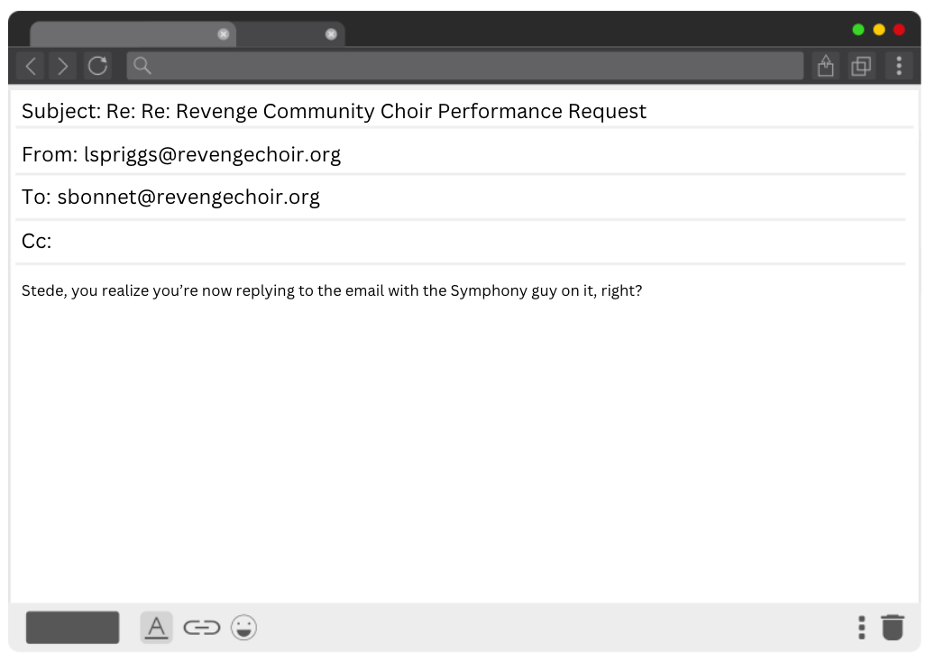

Subject: Re: Re: Revenge Community Choir Performance Request

From: [email protected]

Cc:

Stede, you realize you're now replying to the email with the Symphony guy on it, right?

Email 6

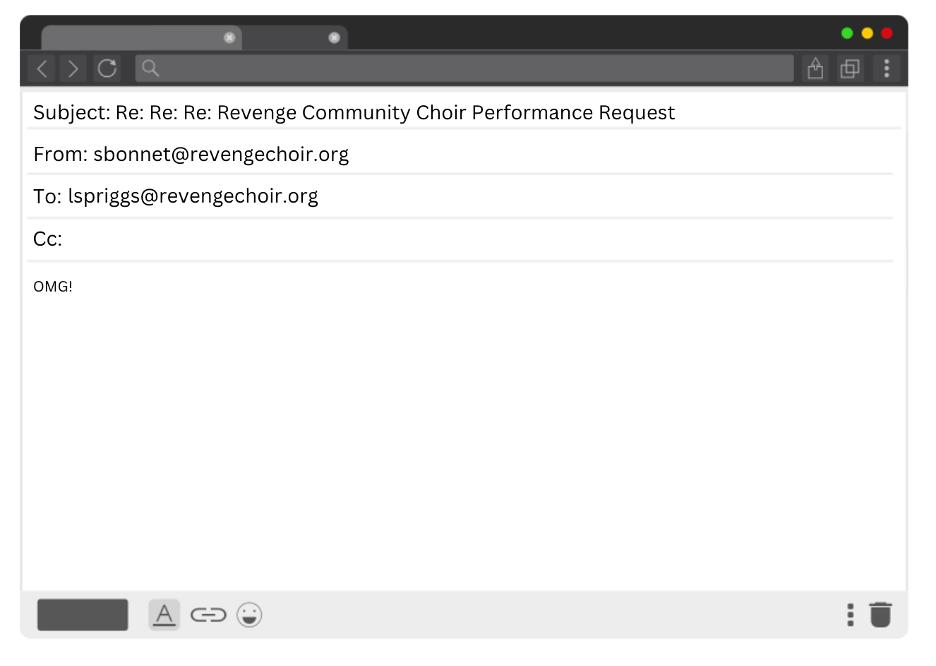

Subject: Re: Re: Re: Revenge Community Choir Performance Request

From: [email protected]

Cc:

OMG!

Email 7

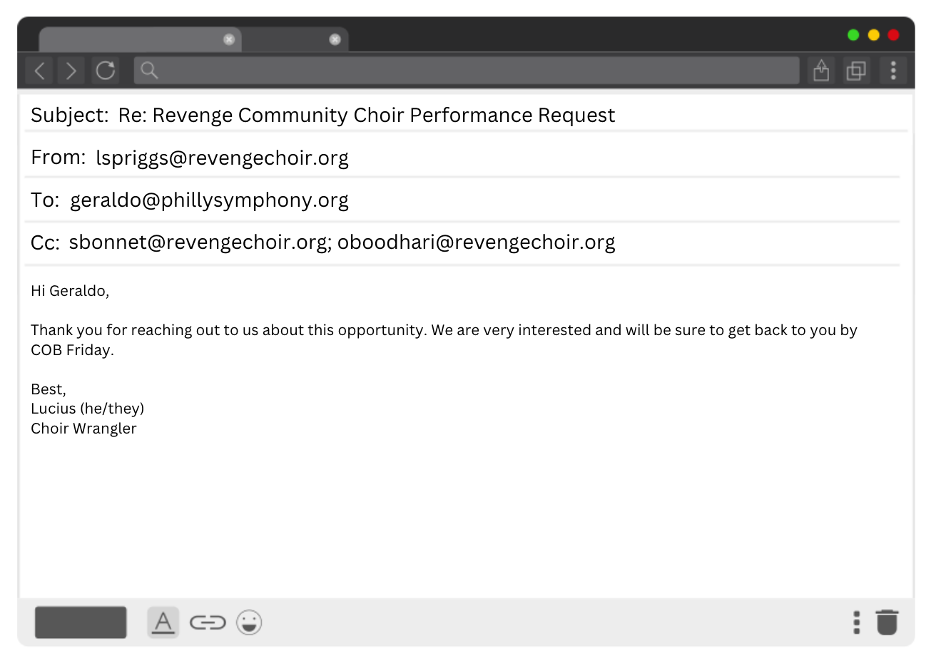

Subject: Re: Revenge Community Choir Performance Request

From: [email protected]

Cc: [email protected]; [email protected]

Hi Geraldo,

Thank you for reaching out to us about this opportunity. We are very interested and will be sure to get back to you by COB Friday.

Best,

Lucius (he/they)

Choir Wrangler

Chapter 5: Movement II

Chapter by ferventrabbit

Notes:

Last time on LIAMK, we were introduced to Revenge Community Choir, the choir Stede leads with Olu as his assistant conductor and Lucius as their trusty choir wrangler. Due to the dissolution of another Philly choir, Revenge has been asked to sing the Brahms Requiem with the Philadelphia symphony (an organization I made up for the fic), which will be guest conducted by none other than legendary maestro Edward Teach. Huge deal! What will our intrepid crew do next?

All digs at Philadelphia are made by me, a lifelong Philadelphia area resident and proud stan 🫡

(See the end of the chapter for more notes.)

Chapter Text

Stede always thought that joy was a tricky thing. It was loud, for one, if not in volume than in scope and feeling, a sound too big for the space he used to occupy. In the past joy had earned him a sideways glance or a scoffed reproach. He wasn’t sure when he stopped caring about that particular feedback loop, if it was all at once or in fits and starts. But now he was practically floating through the Gayborhood, all but skipping across the rainbow crosswalks even as cars beeped behind him.

The Philadelphia Symphony, he thought, hardly believing it. He found himself laughing out loud, completely unbidden. He remembered feeling something like this the first time he conducted a piece in undergrad — Ave Verum Corpus, if he had it right. And maybe that was it, the moment he lifted the veil on joy after all those years. The people in the room — his professor, fellow students — seemed as held by it as he was. He’d witnessed those moments before, from distances that once felt insurmountable. But Stede felt something click into place as soon as he gave the downbeat.

Maybe he wasn’t brave enough to name it then — forbidden words like joy can be forgotten, swallowed. Music could be relentless that way, he’d found. It poked around in the dusty corners of your brain, plucked at memories you thought you’d buried and sifted through the feelings that accompanied them. It demanded honesty, even when the truth bruised and chafed. Stede had thicker skin now, he thought, and he’d found a place for joy to settle in, kick its feet up for a while.

Stede’s phone buzzed in his bag, and Stede nearly tripped trying to retrieve it. Last night he vowed never to go more than three seconds before checking it when it beckoned.

Mary: Hey, 7pm still good tonight?

Stede: I’m so sorry Mary, rain check? The choir was asked to do a “gig!” That’s what they call it in the biz 😎

He’d barely sent the text when his phone started buzzing again, this time with Mary’s name on the center of the screen. He jogged across the street, stopping just outside the Kimmel Center to gather his wits and answer the phone — ignoring Mary’s call would all but guarantee ten more in its wake.

“Hey, what the fuck?” Mary said as soon as Stede picked up. It would be an alarming greeting coming from anyone else. From Mary, it was a full-throated “top of the morning!” with a congratulatory bent.

“I know!” said Stede. “I know, Mary. I can’t quite believe it, and I’m standing outside the Kimmel as we speak!”

“The Kimmel?! Wait, have you guys ever performed there?”

“Of course we haven’t!”

“What do you mean ‘of course?’” Mary asked. And Stede could practically see her rearing to face him with a raised eyebrow. “The choir’s great, Stede. You’ve put in so much work. I’m not surprised you’ve been asked to sing there, not in the least.”

Stede’s friendship with Mary was comforting for many reasons, but chief among them was her (sometimes brutal) frankness, her unreserved opinion grounded in what she truly felt and believed. Mary would never lie to him, Stede knew. The only buttering up she was wont to do was related to English muffins or, bizarrely, Ritz crackers. It had taken him a while to trust that sincerity, especially when it was complimentary. He tamped down on the voice that sometimes lingered even now, the one that sounded suspiciously like his father.

“You’re right,” Stede said. “The choir is great.”

“Thanks to you.”

“Well —”

“Stede,” Mary interrupted. It was as if she were standing in front of him, regarding him with a familiar blend of fondness and impatience. “I might not know much about music. But I do know you. You built that choir from the ground up.” Then she dealt the final blow — a fell swoop of kindness: “You deserve this.”

That was a harder pill to swallow, wasn’t it? Forget a spoonful — this felt like a truckload of sugar to help the medicine go down, so much that he might choke on it. Joy was one thing — accepting that he was worthy of it was quite another.

Stede conceded that Mary did know him, perhaps better than anyone. But it was a two way street, and he knew better than to argue. “Thank you, Mary,” he said, meaning it. He wasn’t sure any of this would have been possible without her, try as she might to deny it.

“So you’re tied up tonight? And not in a fun way?”

“Is there a fun way?”

“Don’t play coy with me, Stede Bonnet,” said Mary. “I knew you in your twenties.”

“Which is why it should come as no surprise to you that I’m asking in all seriousness,” Stede said. Mary laughed into the receiver, loud enough that Stede held the phone away from his ear. By the end of the call he promised to make it up to her with a trip to the piano bar by his place in lieu of dinner ( “and no recruiting singers!” she demanded over his protests). Apparently Stede’s overtures to some of the tenors at the bar were easily misconstrued.

Stede slipped his phone into his pocket and walked to the front doors. He remembered when the Kimmel Center first opened. He’d been home from Yale for winter break (if Mary’s couch counted as “home”) and did a double take when his taxi drove down Broad Street. He marveled at the vaulted glass roof, the jutting balcony that overlooked the street as if Philadelphia itself was the performing act. He nearly tripped over himself when he walked into the main hall for the first time. He noticed the organ first, of course, the pipes like shards of silver reaching up from the choir loft. And the ceiling above it — Stede was still taken by it, each and every time. He recognized the shape of the ceiling as a cello almost immediately, its curved lines and the tiered seats below it tracing the bouts of the instrument, the panels of lights in the center like a bass bar in glowing relief.

But the stage was — god, you could hear it, couldn’t you? Even lined with empty chairs, with music stands askew and the house lights humming overhead, the space held the music that had been there before, that had yet to come. He could describe how it looked — the light wood floor and the thick panels behind it, how it widened as it got closer to the audience like a soundwave. But the word that stuck with him most was possibility . It was something he’d been chasing — in one way or another — since he listened to an orchestra tune for the first time. Mary asked him if he'd get a fancy gold baton when he got his chance to conduct on that stage. “Oh, I don’t think I’ll be up there anytime soon. Or ever, really,” he’d said at the time.

He certainly never thought he’d make it this far.

He reached out to open the door, but found that his hand was shaking. Ridiculous, he thought. But which part? The fact that he was suddenly too nervous to enter a building he’d visited a hundred — no — a thousand times, or the fact that he’d been asked here at all? He was oscillating between the possibilities when Olu rounded the corner at a casual stroll. One of these days Stede was going to ask him how to tap into this state of “chill,” as Lucius called it.

“Stede,” Olu said, offering a brief wave. “Alright there?”

“Yep!” Stede answered in a voice at least a half step too high to pretend at nonchalance.

Olu, to his credit, didn’t miss a beat. “You know, I’ve sung this here before,” he said as Stede held the door for him. “In my sophomore year. A couple of us were asked to sub for the singers who had to drop out at the last minute.”

“Is that so?” said Stede. “No rehearsals needed for you then — I’m sure you can sing it by heart.”

Olu chuckled, but didn’t correct him. He shrugged as they approached the lobby. “It was over ten years ago,” he began. “But I listened to it last night, and every note came back to me. I can’t say the same for the German — I’m hopeless with an umlaut. The music, though.” Olu stopped and looked up, as if he was flipping through the pages of the score from memory. Stede followed his gaze, squinted as daylight streamed in through the glass arches above them. “It’s one of those , if you know what I mean.”

Stede nodded, blinking against the morning sun. “I do,” he said. “I know exactly what you mean.”

He and Olu walked past the entrance to the smaller theatre at the front of the building, past the cafe and the tables and chairs clustered outside the main concert hall. There were a few people milling about — box office staff printing will call tickets for tonight’s concerto, tourists marveling at the expanse of glass overhead. Stede wondered if they knew what he was doing here, if they could tell just by looking at him that this might be one of the most important days of his life. He and Olu chatted quietly as he walked, but he might as well have been shouting at every person they passed: I was asked to be here! My choir is singing here! It seemed impossible that no one else could feel the energy zipping through him — it felt huge and thrilling and terrifying, and seismic enough to send shockwaves bouncing off the ceiling and down into the floor. But the ticketers kept clicking their keyboards as the printer whirred beside them, and the tourists wandered out onto Broad St. without a backward glance. A typical Thursday for the rest of the world, it seemed.

“It’s in the administrative offices, right?” Olu asked.

“Yes, let me…” Stede started patting his pockets in search of his phone, panicking briefly when he didn’t feel it before he remembered that it was still clutched in his hand. He held it up in front of him, as if proving to himself and Olu that he’d known it was there all along.

“I’ve got it, mate,” said Olu, who’d managed to open his email in the time it took for Stede to ride this particular rollercoaster back to the starting gate. “Looks like it’s up on the mezzanine.” Olu nodded toward the wooden staircase on their left that led to the second floor.

“I think I’m a bit nervous,” Stede said as they climbed the first few stairs. “But then again, aren’t I always?”

Olu glanced at him, offered him a small smile. “I wouldn’t say that. You care. A lot. It brings things close to the surface, doesn’t it?”

And if that wasn’t one of the nicest things anyone had ever said to him, Stede didn’t know what was.

Olu led the way toward a door at the end of the open corridor, where they flagged down an usher to swipe them into the back offices. They walked past a practice room where someone was playing a snippet of Mendelssohn, past the library office where a group of interns was sorting sheet music into ever-growing piles.

Stede was always amazed by the endless activity in concert halls like this, where music was only a portion of the goings on. There was always someone folding programs, or setting up super titles, or restringing a violin. Stede had visited the Franklin Institute as a child once, and walked through the replica of a human heart with its fist-sized vessels and atriums big enough to fit two-by-two. He could almost map the anatomy of this place to paths he took in that exhibit, could almost feel its heartbeat keeping time.

Olu checked his phone, then stopped them in front of a closed office door. “Have you ever met her?” Stede asked him.

Olu scuffed his shoe against the floor, chuckling under his breath. “Who, Jackie? Oh, yeah. We’re mates,” he said. Stede wasn’t entirely convinced of that. He looked uncharacteristically abashed and seemed to be waiting for Stede to make the first move, door knocking-wise. Stede made a mental note to investigate at the first opportunity, then steeled his nerves and rapped on the door with his knuckles in quarter eighth-eighth quarter quarter rhythm.

“Really, Stede?” murmured Olu. “Shave and a haircut? You couldn’t go with a more business-y knock?”

“It’s the universal knock of friendliness!” Stede whispered.

He heard heeled footsteps and a creaking chair from inside the room. “That better be my latte, Geraldo!” someone shouted. Stede and Olu had enough time to spare each other a nervous glance before the door swung open. He’d been introduced to Jackie Española at a charity event for the symphony — had spoken to her (or at her, maybe) about the youth choir he was thinking of starting. As he stood in front of her now, Stede was certain that she had no earthly idea who he was.

Stede waited for a greeting and received a raised eyebrow for his trouble. He supposed that counted.

“Hey, Jackie,” said Olu. “Good to see you.”

“Oluwande Boodhari, as I live and breathe,” said someone from behind them. Stede turned to see a man carrying a drink holder stacked high with coffee cups, his brow dotted with sweat.

“Geraldo,” said Jackie, extending her hand. The man — Geraldo, evidently — performed an impressive series of contortions to extract one of the coffee cups without toppling the others. “Did you book a meeting on my calendar before noon? On Friday eve?”

“Only because —”

Jackie took a sip of her latte and held up a finger, nearly bopping Stede on the nose in the process. “We’ll discuss this later,” she said, and ushered Stede and Olu into her office before shutting the door in Geraldo’s face.

“So you know him too, it seems,” Stede said to Olu as they walked through the door.

“He was in my class at Temple,” Olu explained. “Where Jackie guest lectured about arts administration, right Jackie? Good times.”

“Good times,” Jackie echoed as she took a seat behind her desk. “That’s not how I remember it. I seem to remember you showing up late to my lectures.” Jackie set her coffee down and drummed perfectly-manicured fingernails on the desk in a slow cascade. “Every” — drum — “single” — drum — “time. Do I have that right?”

“Late is a strong word, isn’t it?” said Olu, rocking back on his heels. “How do we feel about ‘delayed entrance?’”

“Not feeling too good about that, no,” said Jackie. She leaned back in her chair and turned her attention to Stede. He was suddenly struck by the sensation that he’d found himself in a knife fight with the equivalent of a limp banana as his weapon of choice. “And who are you supposed to be?”

“I’m Stede,” he said, practically choking on his own name. “Stede Bonnet. I’m the Artistic Director of Revenge Community Choir.”

“Stede Bonnet,” Jackie repeated. She took a — slow — sip of her latte as she considered him. Then she outstretched her hand and gestured to the two empty chairs in front of her desk. Stede and Olu moved to take their seats, colliding with one another briefly when they tried to squeeze through the space between them. Jackie seemed unfazed. “So,” she said. “You’ve come to save the day, is that right?”

Stede scooted forward in his chair, nearly tipping it over. “Well,” he began, “I wouldn’t say that. You don’t strike me as the kind of person who needs saving.”

“I’m not,” said Jackie, with an assuredness that might as well have been a shouted declaration. “But this symphony is.”

She sighed and rose from her chair, looking out of the tall windows behind her desk. They faced a building with dark, empty offices, open floor plans with cubicles that looked like they might start growing moss. Sometimes Stede forgot the pandemic for minutes at a time, or at least forgot how stark the contrast was between the world before and after. He saw the effects here, clear as day. He guessed that Jackie was seeing them too. She turned back around, and Stede swore he could see the barest hint of weariness behind her eyes.

“I won’t sugarcoat it. It’s dire as fuck right now. I have the best musicians in the world — the best — and I couldn’t fill a house even if I was paying for butts in seats. The Chorale disbanding is just the cherry on top of a shit sundae.”

Stede sat in stunned silence for a moment — not necessarily at the sentiment, but the candor with which it was expressed. That…well, that…

“That’s about the size of it,” said Olu, as if picking up where Stede’s brain left off.

“Yep,” Stede agreed.

“Sorry,” Jackie said as she retook her seat. “Normally I’m sunshine and rainbows.”

“Oh, sure,” said Stede. “This is just a…minor blip. Well, or a major blip, given the extent. But minor given the mood, I think. Maybe D minor?”

“Well…” Olu began, though seemed too visibly pained to continue.

“Listen,” Jackie said, leaning her arms on the desk. “If I were you, I’d want to hear the truth. And the truth is, we need this concert to usher in a new age for this orchestra. And I’ll be honest, I’m not sure if your choir has performed at this level before. Are you up for it?”

That’s it, Stede thought. That’s the question that he’d been too afraid to ask himself since he read (and reread) the email from last night, the question lying in wait behind the front door of the Kimmel, down the carpeted hallways, here in Jackie’s office. He was years removed from his parents’ box at the Academy and from long stretches at boarding school that felt more like psychological experiments than the best education money could buy. And Stede was proud to say that he’d chosen his own adventure despite the fixed script he’d been given: music (as an interest!), sports (no-contact, of course!), legal studies, marriage (to a woman!), children playing on a well-manicured lawn.

But doubt was one of those houseguests that you could never seem to get rid of — invited to every party out of habit, never quite rude enough to be removed from the list, passive aggressive in the way all of the Bonnets’ Main Line neighbors had been. It pretended at self-effacing humility, or as the eminently reasonable recognition of one’s own limitations. But Stede saw the glint of sharp teeth behind its placid smile, the grip of its handshake tight enough to crush his hand in its grasp.

Fighting it seemed to be no use, most of the time. And he reminded himself that he might doubt whether he was up for it, all the way up until the moment of truth had come and gone. He could doubt himself. But his choir? Never.

“We’re up for it,” Stede said, leveling Jackie with as confident a stare as he could muster.

“Absolutely,” added Olu. He didn’t miss a beat.

Jackie didn’t react at all, as far as Stede could tell. Who knew — maybe no reaction was a celebration in and of itself. He supposed it could always have gone the other way — Jackie seemed capable of ushering in a modern ice age with a cutting remark. Instead, she stood as she drained the last of her coffee, then considered each of them briefly before she moved out from behind the desk. “I hope so,” she said as she passed their chairs, then flung the office door open and shouted for Geraldo so forcefully that Stede had to marvel at the breath support. Geraldo stumbled in moments later, clearly used to being summoned with no time to spare.

“Alright boys,” Jackie said as she returned to her desk. “Let’s get to work.”

Stede was never good at logistics. That was Lucius’ specialty. He struggled through the next hour of scheduling rehearsals and sound checks and music pickups with a growing sense of dissociation, like an astronaut floating farther and farther away from the spacecraft as the tether pulled taut enough to snap. Olu kept up as best he could, and held his own against Geraldo’s occasional digs about the choir’s lack of experience — “oh, you don’t have a Director of Operations? Jackie, are you sure we can work with these guys?” — and Jackie’s vaguely threatening rebuttals — “we won’t be doing anything if you question me in front of our guests, I’ll tell you that.”

The more they talked, the more the sheer scope of this performance loomed for Stede. They’d occasionally performed with full orchestras, but never one of the symphony’s scale and prestige. The largest hall Revenge had ever performed in seated eight hundred people — this one seated three times that. This was — quite literally — the biggest platform the choir had ever had.

And he hadn’t even allowed himself to think about Edward Teach.

Blackbeard, they called him, partly an unimaginative nickname for someone with a black beard, but mostly a moniker that evoked a profound sense of awe. Stede had the chance to see him with the Boston Symphony, back when Stede was still at Yale. The entire department talked about him like he was already among the greats. All the conducting students went up to see the performance, even though Stede was a reluctant Shostakovich listener at best. But Stede could never forget what he saw that night. Almost as soon as Maestro Teach walked onto the stage, the entire audience was captivated.

Stede remembered seeing Benjamin Hornigold — Teach’s mentor — years ago, as a child. He’d been impressed then. But this was something entirely different. This was raw, unmitigated talent, so potent that it was almost another instrument in the array. Stede liked to think that he knew as much about conducting technique as anyone else — more, even. But he would never be able to capture this in an academic text. He couldn’t even articulate it to his classmates on the way back to New Haven, as much as he tried. “He…I don’t know, he just…” It was the best he could do at the time. Now, after following Teach’s career ever since and thinking back on that night, he thought he might have something worthwhile to say.

“Edward Teach, he…” Stede began as he and Olu descended back to the Kimmel Center lobby. “There’s music in him. Just living there right under the surface, ready to be called up at any moment. One flick of his wrist and it’s out in the world, tuned and voiced in a way no one has ever heard it before.”

“You’ve seen him live?” Olu asked.

“Mmhmm,” said Stede. “At his Boston Symphony premiere. He was only twenty-five at the time, can you believe it?”

Olu scoffed, pushing the front door open with his shoulder. “Cut to me at twenty-five making my First Presbyterian Church premiere.”

“Right,” Stede laughed. “I was probably down the street at the Second Presbyterian, not even First material.”

He and Olu made their way to the tiny choir office on Market to start planning the choir announcement and the emergency (and likely painful) board meeting slated for later in the afternoon. There was so much to do that Stede almost felt like the pendulum had swung to the opposite end of the spectrum: so much to do that nothing could possibly get done. Might as well stroll down Broad and smell the roses. Or, in this case, the aroma of downtown Philadelphia: flavored vape smoke, car exhaust, and trash waiting for an illusory pickup. And maybe not stroll so much as dodge obnoxiously loud four-wheelers careening down the street and, weirdly, a gentleman dressed as Elmo with little to no depth perception. Yep, Stede thought. I wouldn’t trade this place for the world.

“Hey, listen,” said Olu when they reached the office building. He placed a hand on Stede’s arm just as Stede raised it to type in the entrance code. “I wanted to say something before we jump in.”

“Oh, we haven’t jumped in yet? Could have fooled me.”

Olu chuckled, nodding slightly. “True. Bit of a trial by fire back there. But I just wanted to say that I know we can do this, Stede. That the choir can do this.”

Stede knew his face was crumpling into what Mary called his “crying cat” expression — even though Stede conclusively proved that those memes were photoshopped (especially the one with the thumbs up), he had to concede the resemblance. He could feel his cheeks dimple, knew his eyes were watering even as he tried to rein it in.

Olu immediately looked concerned, tightening his grip on Stede’s arm. “Mate, are you okay? I’m sorry.”

“Yes, of course,” Stede said, though he was well aware that his face was what most human beings would describe as “sad.” A textbook case, he’d wager. He couldn’t quite say why hearing lovely things made him look like the world was ending. He shook his head, wiped at his eyes. “I’m wonderful, Olu, really. I appreciate it so much.”

“Don’t mention it. I mean it,” said Olu. He gave Stede’s arm a squeeze just as Lucius rounded the corner at full tilt with a veritable mountain of scores in his arms.

“Hey,” he said when he stopped alongside them. “We can’t cry in the doorway of the office, any other doorway on Market is fine.”